Eight Ways the United States Can Help Mobilize Loss and Damage Funding

The United States has a particular responsibility and capacity to lead the global funding response to climate impacts. Here's how.

EU humanitarian aid reaches survivors of devastating floods in Pakistan

© European Union, 2022 (photographer: Abdul Majeed)

Co-authored with Rennie Jones, NRDC's 2023 Moran Environmental Fellow. Rennie is a Masters in Environmental Management candidate at the Yale School of the Environment, specializing in international climate policy and climate migration.

Hurricanes, wildfires and even slower-onset climate impacts, like rising sea levels, are outstripping the ability of many communities—particularly the poorest and most vulnerable—to cope. All around the globe, this means loss and damage to lives, livelihoods, property, and cultural heritage.

Climate impacts that cause loss and damage

Rennie Jones

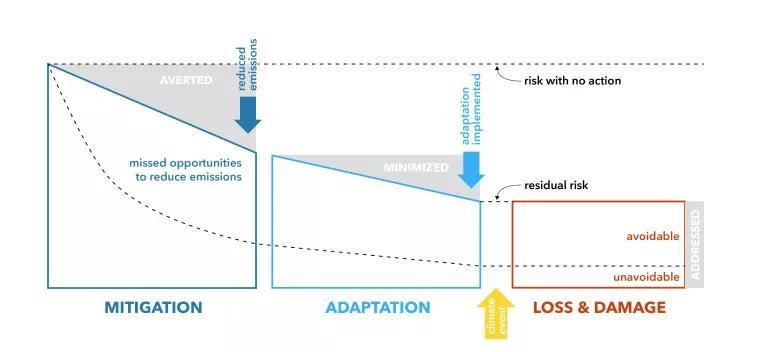

While we still need to cut emissions (mitigation) and reduce the severity of climate impacts (adaptation), we also clearly need to be ready, financially and otherwise, to address the fallout of climate change that we can’t avoid.

Mitigation and adaptation help avert and minimize harm, but there will still be loss and damage

Rennie Jones, adapted from J.A. Richards (2023) How Does Loss and Damage Intersect With Climate Change Adaptation, DRR, and Humanitarian Assistance?

At COP27 in 2022, governments agreed to establish funding arrangements to assist vulnerable developing countries in responding to loss and damage, including creating a dedicated fund to address loss and damage. At COP28 in 2023, countries formally adopted the governing instrument of the Fund, allowing it to get to work this year.

With the architecture for organizing the global response to loss and damage coming into focus, the key question now becomes how to generate sufficient funding.

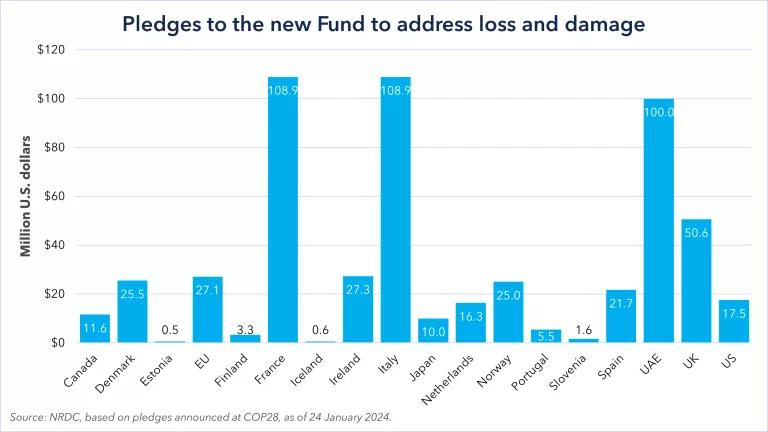

At COP28, governments pledged $661.9 million to the new Fund, and around $130 million for other arrangements to support loss and damage – close to $800 million in all. But with estimates of loss and damage costs in the hundreds of billions of dollars per year, more funding will be needed.

Joe Thwaites/NRDC

As the biggest cumulative emitter of greenhouse gas emissions and the largest economy in the world, the United States has a particular responsibility and capacity to lead. In addition, failure to help vulnerable countries address the growing impacts from climate change brings increasing diplomatic, economic, and security costs. In the absence of U.S. leadership on loss and damage, it leaves a void for rivals to shape rules and build alliances that undercut U.S. influence. Unaddressed climate impacts disrupt supply chains, raising the price of commodities and undermining global economic stability. And climate disasters can exacerbate underlying stressors that drive conflict and force people to migrate.

Despite many good reasons to show solidarity in helping vulnerable countries deal with climate impacts, political deadlock has meant the U.S. has not been very successful in delivering climate finance, lagging behind the rest of the G7 in what it contributes on a per capita and share of GDP basis.

At COP28, the U.S. announced a $17.5 million pledge to the new Fund to address loss and damage, along with $4.5m for Pacific Resilience Facility and $2.5 million for the Santiago Network. These contributions are important, but the U.S. will need to do much more if it wants to live up to its international responsibilities and maintain its climate leadership.

Given challenging domestic politics, there is a need for innovative thinking about alternative ways the U.S. can step up and play its part in generating funding for loss and damage. Here, we explore some potential solutions, focusing on three groups of proposals: expanding existing systems to provide financing; addressing debt; and raising revenue in innovative ways.

For each, we explain the idea, review the status of discussions including the U.S. government’s position, and explore what further questions remain.

Expanding Existing Systems

There already exists a complex humanitarian system for responding to disasters around the world. But it is under-funded and over-stretched to respond with increasingly severe natural disasters driven by climate change.

1. Anticipatory humanitarian aid

What is it?

Disaster response plans and payouts based on pre-defined triggers (such as a hurricane of a certain size) could facilitate much quicker disbursement of funding after a disaster.

Status

- The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs is working on anticipatory action within the humanitarian sector.

- Small Island Developing States support the idea of direct payments (insurance payouts) to affected communities following a disaster.

- The U.S. has argued that the existing humanitarian architecture, which designed for emergency response to natural disasters, should be used to deal with rapid-onset loss and damage.

Key questions

- Will this approach generate more funding, or just spread the already under-funded humanitarian system even more thinly?

- How should the triggers for making humanitarian aid more anticipatory – so funding flows in advance of or as soon as possible after a disaster – be defined? Trigger-based response mechanisms have a mixed record, with funding often not flowing as quickly as intended.

2. Non-economic measures to address non-economic losses

What is it?

Make support for addressing loss and damage available in non-financial ways, such as by providing special visas for people displaced by climate disasters.

Status

- The concept of resettling people displaced by climate change has been raised in discussions of loss and damage.

- Australia and Tuvalu recently agreed a treaty that allows 280 residents to migrate from Tuvalu to Australia each year. At this rate, it would take around 40 years for all of Tuvalu’s approximately 11,200 citizens to relocate to Australia.

- The U.S. has emphasized that the loss and damage fund should address slow-onset events and displacement, and the need to look at non-economic measures to address non-economic losses.

- In 2021, U.S. Senator Ed Markey and U.S. Representative Nydia Velasquez proposed legislation to address global climate-driven displacement.

Key questions

- Would the U.S. be willing to issue special visas or amend the current humanitarian visa criteria to cover climate-displaced peoples?

- What other non-economic measures, such as preservation of cultural heritage, could the U.S. support?

3. Citizen crowdfunding, contributions from state and local governments, philanthropies, and the private sector

What is it?

Enable nonfederal U.S. sources, such as state and local governments, philanthropies, the private sector, and citizens to contribute to loss and damage funds.

Status

- Most climate funds accept funding from government sources only. This can include state and local governments. For example, the Belgian regions and the Canadian province of Quebec have contributed to several UN climate funds. The city of Paris contributed to the Green Climate Fund (GCF).

- The Adaptation Fund can accept contributions from individuals via a donation platform.

- In 2017, after the Trump Administration announced it was withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, the U.S. cities of Seattle and Washington D.C. passed resolutions to explore the possibility of contributing to the GCF.

- Massachusetts has been considering a bill that would allow state taxpayers to allocate a portion of their tax refund to the Least Developed Countries Fund.

- Multilateral funds in the health sector, such as the Global Fund and GAVI receive considerable funding from private companies and philanthropies.

- The U.S. supports ensuring that the loss and damage fund can accept funding from a wide range of sources, in addition to national governments.

- The Transitional Committee’s consensus proposal instructs the trustee of the fund to “ensure that the Fund can receive financial inputs from philanthropic foundations and other non‐public and alternative sources, including new and innovative sources of finance.”

Key questions

The loss and damage fund Board may decide to pass additional policies to encourage and receive innovative sources of funding, such as establishing a donation button on the website, and outreach efforts to potential contributors. U.S., federal and state law may restrict the ability of sub-national governments contributing to international organizations.

Debt Sustainability

Climate vulnerable countries are in a climate investment trap. High borrowing costs increase the likelihood of indebtedness and make it harder to invest in building resilience to climate impacts. This leaves countries more vulnerable to climate disasters, and when they are hit, they lack fiscal space to spend on disaster response or invest in recovery, and often face downgraded credit ratings, making borrowing even costlier. Addressing sovereign debt can enable vulnerable countries to focus more on disaster recovery and reconstruction, as well as longer-term resilience investments, instead of debt servicing.

4. Debt-suspension clauses

What is it?

Inclusion of “pause clauses” in sovereign debt instruments that suspend debt service for period of time when a country is affected by a natural disaster of a certain threshold. This provides developing countries the fiscal space to prioritize vital investments in disaster response and recovery.

Status

- There is growing support for debt-suspension clauses, particularly since they were popularized as one of the key proposals in the Barbados-led Bridgetown Initiative.

- Throughout 2023, a growing number of countries and institutions, including the UK, France, Canada, the World Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank have committed to implement debt suspension clauses in their lending. This includes the U.S., which committed to include climate disaster debt suspension clauses in their bilateral lending and export credit finance, and has also expressed support for inclusion of climate-resilient debt clauses in private lending.

Key questions

- Does the U.S. commitment to incorporate debt clauses in its international finance include all bilateral financing?

- Will suspension clauses only be available to particularly vulnerable countries, or all countries?

- Will the US use its significant influence over multilateral financial institutions in which it is a shareholder to push them to include climate-resilient debt clauses in all their lending?

- Can debt-suspension clauses only be used once in the lifetime of the debt, or multiple times?

5. Debt-for-nature swaps / Debt-for-climate swaps

What is it?

Creditors forgive or restructure debt in return for the borrowing country agreeing to invest in climate or nature protection the resources that would have been spent repaying the debt . Borrowing countries benefit by gaining increased fiscal space, while creditors have an assurance that the country will invest in activities that have (often global) environmental benefits.

Status

- Debt-for-nature swaps were first developed in the late 1980s, but have only been used on a limited scale. As of 2021, debt-for-nature swaps have covered just $3.7 billion in the face value of debt.

- In recent years, interest in debt-for-climate swaps and the size of transactions has grown considerably.

- The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation has supported several large debt-for-climate/nature swaps. In 2021, it backed a $550 million deal with Belize, and $550 million for ocean conservation this year in Gabon, as well as $656 million for the Galápagos marine protected area in Ecuador, the latter being the largest ever debt-for-nature swap.

- IIED have estimated that swaps have the potential to unlock $105 billion for spending on climate and nature in 58 vulnerable developing countries.

Key questions

- Debt swaps are complex to negotiate and have only been used at modest scales. To what degree can they be scaled up to free up more resources?

- Debt swaps have been critiqued for undermining sovereignty of borrowing countries, since the deals cede some decisionmaking over policy and investment to other governments or private actors. Can debt swaps be structured in a way that upholds principles of country ownership?

Innovative Levies

Innovative levies are potential new sources of concessional funding which could be contributed to loss and damage fund. They could help address “pay-for” restrictions, where governments self-impose requirements that expenditure be fully paid for by increased revenues or cuts to in spending elsewhere

6. Shipping levy

What is it?

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) has been discussing a proposal to impose a levy on shipping. The levy would be based on mandatory contributions by ships trading globally for each ton of carbon dioxide they emit. The proceeds would go into an IMO Climate Fund, which would help subsidize the shipping sector’s emissions reduction efforts, and also to developing countries.

Status

- There is growing support for an IMO levy, with 22 countries signing a statement endorsing it in June 2023.

- The U.S. has stated that it is "positively inclined to the discussions happening in the IMO on a maritime pricing mechanism."

- However there is significant pushback from a number of major emerging economies, Including China, Brazil, South Africa and Saudi Arabia.

- Negotiations in the IMO failed to reach an agreement on the levy in their July 2023 meeting, and discussions on the measure are ongoing.

Key questions

- Since all countries would effectively be contributing, rather than only wealthier countries or larger emitters, some governments have raised concerns about how equitable the levy would be.

- What provisions could be implemented to ensure that a levy doesn’t adversely affect vulnerable and shipping-dependent developing countries?

- Given an IMO levy would be outside of UNFCCC control, how and what proportion of the revenues would countries direct to loss and damage funding?

7. Aviation levy

What is it?

Many countries apply taxes or levies on air travel as a way to generate funding. Given the high emissions intensity of flying and its relatively elite nature (only 11% of the world’s population is estimated to fly in a given year), a levy to support loss and damage could be a good way to operationalize the “polluter pays” principle. Levies could be applied unilaterally, or through a multilateral process such as in the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO).

Status

- There have been multiple studies in various countries proposing aviation levies to raise climate funding (both domestic and international), but this has not had serious discussion within multilateral bodies.

- A number of countries, including France and the Republic of Korea, have voluntarily applied an international airline passenger levy, which raises $400 million annually, with proceeds primarily going to UNITAID to finance health programs in developing countries. This model of using domestically-applied airline levies to contribute to international funds could be replicated for loss and damage.

Remaining questions

- Has the U.S. discussed the possibility of an air travel levy to generate funding for loss and damage?

- To what degree would such a tax or levy require Congressional approval?

8. Extractive industry levy or windfall tax

What is it?

A solidarity levy would impose a charge on each ton of coal, barrel of oil or cubic meter of gas extracted at a level that would reflect the embodied CO2. Another concept is a windfall tax on energy industry unexpected profits. A global flat tax on fossil fuels at $6 per ton of embodied greenhouse gas emissions is projected to generate $150 billion annually. This levy rate is far below the estimates of climate damages caused by fossil fuels, which the U.S. government currently put at $51 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e).

Status

- Carbon pricing schemes currently cover 23% of global emissions, raising $95 billion in revenues in 2022. The UK expects to generate $80 billion from a windfall tax on energy companies introduced in 2022. Most governments spend revenues domestically, but European governments spend around 1% (~€200 million per year) of their revenues from the EU Emissions Trading System on international climate action.

- The U.S. has mentioned an extractive industry levy as a possible contributor to loss and damage funding.

Remaining questions

- How does the U.S. envisage levies operating – governments acting unilaterally to establish them, or with international coordination? Would the U.S. be willing to join in if other countries cooperated to establish a levy?

- How would the U.S. address domestic political hurdles, given the challenges the U.S. has faced in advancing carbon tax proposals?

Where now?

These proposals capture just a few of the ideas circulating on ways to generate funding for loss and damage. Each faces political and technical challenges, but given the deadlock in scaling up “traditional” sources of appropriated climate finance, there is a need for fresh thinking. The good news is that most of the proposals are already being used to generate financing for other areas, so have proven themselves workable. The question is whether they can be adapted and scaled up to meet loss and damage needs.

As it considers how it will contribute loss and damage finance, the Biden administration should consider these and other more innovative approaches to generate funding. It should continue to engage with Congress on the potential for regular appropriations of climate finance, but also gauge support for alternative funding approaches. And the administration needs to engage the rest of society – state and local governments, private sector, philanthropies and individual citizens – on how, at every level, we can make meaningful contributions to addressing climate impacts around the world.

If the U.S. wants to continue to claim the mantle of global leadership, it needs to show leadership in addressing the impacts of its actions around the world.