Environmental Justice in Chicago: It’s Been One Battle After Another

Cheryl Johnson and Peggy Salazar have been speaking out against pollution and environmental injustice for decades, but the city of Chicago sees their South Side neighborhoods as sacrifice zones. They are demanding change.

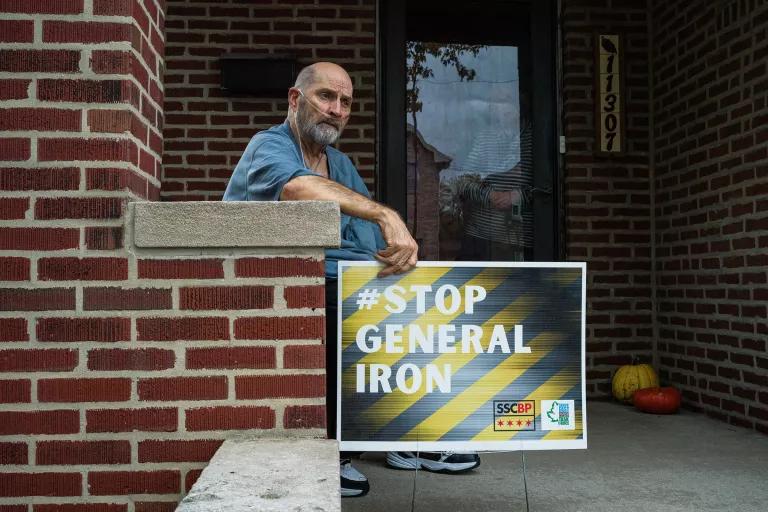

Protestors at the Youth Rally Against General Iron in Chicago’s South Side, October 25, 2020

Cheryl Johnson and Peggy Salazar, lifelong residents of Chicago’s South Side, grew up in some of the city’s most polluted neighborhoods, in the shadow of dirty industries, including steel mills, coal plants, manufacturing plants, and storage facilities.

The women now lead two of Chicago’s oldest environmental advocacy groups. Johnson is the executive director of People for Community Recovery (PCR), which was founded in 1979 by her mother, Hazel Johnson. Salazar is the executive director of the Southeast Environmental Task Force (SETF), formed in 1989. Their work includes demanding that city representatives and industry leaders undo—and stop perpetuating—decades of unfair policies and practices that have left communities of color and low-income residents overburdened with toxic air pollution and other environmental health hazards.

In Chicago, Black and Latino residents are more likely to live close to industrial pollution and have chronic health conditions, such as asthma, according to the Chicago Department of Public Health. A recent report issued by the city earlier this year noted that “structural racism and economic hardship” are “making it more likely for certain people to live in polluted communities.”

Here, Johnson and Salazar give powerful accounts of what it’s like to grow up and live in neighborhoods deeply impacted by environmental racism. Their tireless efforts not only inspire but also help envision a path forward—to right past wrongs and create healthier, more equitable communities across the city.

Cheryl Johnson

A Mother Who Began to Ask Questions

I grew up in Altgeld Gardens, a housing project on the far South Side that was originally built for Black World War II veterans. In 1969, my father died from lung cancer at the age of 41, and my mother, Hazel Johnson, started wondering why so many people in the area have died of cancer.

She started doing research. She learned that the South Side had the highest incidence of cancer than any other area in Chicago. She wanted to know why a lot of people had asthma and other health problems. She learned that our area had 50 documented landfills, hundreds of hazardous waste sites, and leaking underground storage tanks. And, all around us, we had industry that constantly emitted air pollution. My mom called our community “the toxic doughnut” because we were completely surrounded. In 1979, she founded People for Community Recovery to raise environmental awareness and help local people impacted by pollution.

“They Tried to Break Her Spirit”

In the early years, it was very difficult for my mother. She didn't have a science background; she was not educated or trained in this area. She just knew that something was wrong.

A New Generation Is Speaking Out

Oscar Sanchez, cofounder of the Southeast Youth Alliance, is rallying youth in his community to take action on the future of Chicago’s South Side.

Tired of the Negative Stigma

The Southeast Youth Alliance came about two years ago when some college students—myself and a few others—started to feel tired of the negative stigma of our community. We were like, “We need to make a difference.”

We focus on environmental and social justice. Our biggest success is that we are revitalizing community engagement. We're doing educational events, community cleanups, and we organize and attend protests. We also put together art fairs that promote local artists and their art. We host community envisioning sessions where we ask folks, “What do you want to see here?” It's not just about our vision—it's about the community’s vision. One of the things we've been talking about is that you shouldn't have to choose between being able to breathe and being able to have a job or having a good quality of life.

Harmed by Pollution

We're so normalized to living in a dumping ground for the city. People say we exaggerate, but we are one of the few places in Chicago where zoning [policies] allow this to happen. If your zoning [policy] says you can dump all of this here, then we're a dumping site. I think of my family. I think about growing up here. I think of my brothers who have asthma. I think of my brothers who played in the baseball field that had large amounts of contaminants.

A City that Doesn’t Care

The Chicago Public Department of Health has failed us. The Illinois Environmental Protection Agency has failed us. They don't care about community input. They don't even care about the environmental burden. It's not even a requirement when it comes to the permitting process to look at environmental burden or to strongly prioritize community input. We have to look at where the resources are going, and our community is under-resourced. I always emphasize that we are literally fighting for scraps. Lincoln Yards, on the North Side, is getting a $1.3 billion investment, and then you have South Chicago—we’re competing with 10 other neighborhoods to get $10 million dollars. That's ridiculous.

Many times, I wanted to fight people for the way they treated my mother. Elected officials would say to her, "Well, the garbage has to go somewhere. Why not your neighborhood?" Or they would claim that the pollutant in the air was not as bad as what she said it was. They treated her so rudely. She would come home crying because someone called her a big-mouthed woman or an ignorant person or told her she didn’t know what she was talking about. They tried to break her spirit—that's hard for a child to see. She would call our local Environmental Protection Agency Region 5 office, but they wouldn't work with her because they had no jurisdiction over the impact that industry had on a community. They were only mandated to regulate industry and to work with academic institutions, but not with a community.

Early Victory for Safe Water

One of our first environmental victories was right next to our community in Maryland Manor, a subdivision bordering Altgeld Gardens, in 1984. For 25 years, the residents there were paying taxes on a sewer line and water hookup that they never had. They had well water that was very contaminated with pollution.

The history of pollution there goes all the way back to the 1860s when [industrialist and inventor] George Pullman used to own the land and had a sewage farm in this area. It was used as a dumping ground for a long time. Testing of the well water showed cyanide and other contaminants. We were able to get the city to install water and sewer lines. It’s interesting that here we are today, over 100 years later, still here on this land, and we are still talking about environmental justice.

Recognition and a Growing Movement

In the early 1990s, my mother began to travel and meet with other community groups. She received President George Bush’s Environment and Conservation Challenge Award in 1992. Being with her at the White House when she received that award is an experience I'll never forget. The previous year, the first National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit took place. It was there that she was first called the “mother of the environmental justice movement.” [Delegates from around the county] all joined together [at the summit] and came up with the 17 Principles of Environmental Justice. That meeting helped lead to President Clinton’s signing of Executive Order 12898 in 1994, which said federal agencies had to consider environmental impacts on communities of color and low-income communities.

Resistance to Environmental Justice

My mother passed in 2011, and about a year after that, there started to be a little more awareness and recognition of the environmental justice groups in Chicago. For decades, the city has been wholeheartedly resistant to recognizing environmental justice, especially under the Daley administration. [Richard M. Daley was the mayor of Chicago from 1989 to 2011.] In fact, during that period, we learned that the Chicago Housing Authority [CHA] had dumped thousands of gallons of PCB waste right in the heart of my community. We had to fight with the city and CHA to clean it up—and to this day, I don’t think it was completed properly.

Current Battles and Planning for the Future

This past year, we joined several local groups and filed a fair housing complaint with the Department of Housing and Urban Development. We are very concerned about the relocation of a recycling facility, General Iron, from Lincoln Park, a wealthier neighborhood, to our area. We talk about the city of Chicago just using our community as a dumping ground for so many years. Why do we always have to get polluting industries in our area? It’s not fair. Land-use practices in Chicago have been discriminatory.

My mother used to say that we know how to dirty up this country, but we don't have the workforce to clean it up. One of the major goals of People for Community Recovery is to create training facilities in the area.

We were the first in the country to bring lead abatement training for workers to the community. We trained nearly 300 residents, and a little more than 80 percent of the folks would get jobs with contractors doing lead abatement. We are also working to promote our community to become a solar community and to have more education about energy efficiency. We are looking at how we can be engaged in the clean energy economy and get residents trained in those opportunities. This is the only place I've ever lived. It's a good community if only the city and the state would invest instead of letting it go.

Peggy Salazar

“We Thought Pollution Was Normal”

I grew up on the South Side of Chicago in the 1950s and ’60s—literally across the street from U.S. Steel. Back then, you could live that close to the steel mills. We didn’t really think about the pollution or how dirty things were, but I remember my mother complaining that when she hung the laundry outside, it would get dirty if she didn't bring it in as soon as it dried.

We thought everybody's neighborhood was as sooty and dusty and drab. It wasn't until I got older and ventured outside of the neighborhood that I realized not everybody lives in an environment like this. It was an interesting awareness, but at the same time, I was still accepting of it because I grew up in it.

A Rude Awakening

In the late ’80s, when the steel mills began to close, I started volunteering with a neighborhood group called the Veteran's Park Improvement Association. With the massive loss of jobs [from the steel mill closures], the organization wanted to keep the neighborhood from declining and keep people from moving away. I started to learn more about how the community was treated. Our local gas utility had done a cleanup of an old coal gasification site in our neighborhood. It removed most of the contamination and then filled it in with gravel. I found out later that we could have demanded much more than that—we could have had it cleaned up to a better level, where it was usable by the public. Our alderman didn't tell us we had that option. I felt like we had been totally let down as a community. Our leaders didn’t fight for us; instead, they were on the side of industry—that was a rude awakening.

From that point on, I said, “I need to educate myself.” I didn’t think we could trust anyone. I was convinced that if this had been in a more socioeconomically advantaged community, it wouldn't have happened. Or residents probably would have been more informed or aware. They take advantage of people not knowing or being educated about the facts.

The Formation of the Southside Environmental Task Force

Marian Byrnes started the Southside Environmental Task Force in 1989. She successfully helped fight off a proposal to pave over a large wooded area for a bus storage facility, stopped a new garbage incinerator from being built, and halted efforts to reopen old city dumps in the area. During my volunteer work with the Veteran's Park Improvement Association, I would rub shoulders with the SETF. Even though I wasn't part of it, I became interested in their work because, after all, this was a dirty, polluted area.

I started volunteering with SETF in the mid-2000s. The term “environmental justice” was not something I was aware of until I got involved. I got to know people like Cheryl Johnson from People for Community Recovery—and heard about her mother. I got to know more history. In 2009, when SETF needed an executive director, I took the job. Every year since then, we have had a battle.

“We're Always Being Dumped On”

We opposed a 33-acre outdoor firing range that the city of Chicago wanted to build, near Hegewisch Marsh Park. We had to fight against a coal gasification plant. The biggest eye-opener for people was the petcoke situation—piles of petcoke were blowing toxic dust all through the neighborhood. Then we had a similar crisis with toxic manganese dust blowing all through the community from a storage facility. Every year, it's something. It's like we're always being dumped on.

All along, I have been trying to just make people aware of the industrial corridor and the impact it has on us—and that other communities don't have the same kind of a situation going on. I remember a volunteer telling me that they never realized how dirty our community was until they went to the North Side, where everything looks so much cleaner. And it’s the truth. In the 1990s, a huge effort was made to green the Chicago River and push out and relocate industry. At the same time, the city was working to preserve the polluting industrial corridor in my community. I think every neighborhood needs reinvestment. I don't like this piecemeal kind of revitalization approach—and when it's not done equally across the board, that's unacceptable. We need to look at the city and think about how to make all the neighborhoods better.

“They Want to Keep Us a Sacrifice Zone”

We had hoped that our situation would improve when Mayor Lori Lightfoot took office in 2019. I'll never forget that we went to her candidate forums and brought up all these issues. She seemed very sympathetic to us, so we were very hopeful. Then she got into office and decided to move forward to relocate General Iron—a very polluting metal-shredding operation on the North Side in Lincoln Park—to our community. General Iron has violated environmental codes, it’s had explosions and fires, and it’s been shut down repeatedly for public health violations. The North Side doesn’t want it. We don’t want it either.

Along with PCR and other local groups, we filed a fair housing complaint with the Department of Housing and Urban Development about General Iron. We’re demanding an end to policies that entrench environmental racism. This is clearly discriminatory and demonstrates environmental racism when the receiving community is already overburdened by industry—and is protesting the relocation. The reason that the city wants to do this is because we have this history. They want to keep us a sacrifice zone.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Chicago has more lead service lines than any city in the country.

Urge Mayor Johnson to replace Chicago’s toxic lead service lines and protect residents!

Sometimes Art Has to Get Gritty—Especially When Big Oil Provides the Muse

Mining for Limestone on Chicago’s Southeast Side? Residents Gear Up for a Fight (Again).

The Particulars of PM 2.5