Five Indigenous Poets Explore Loss and Love of their Native Lands

From saguaros to sacred waters, the writers weave their personal relationships to the environment with the ancestral.

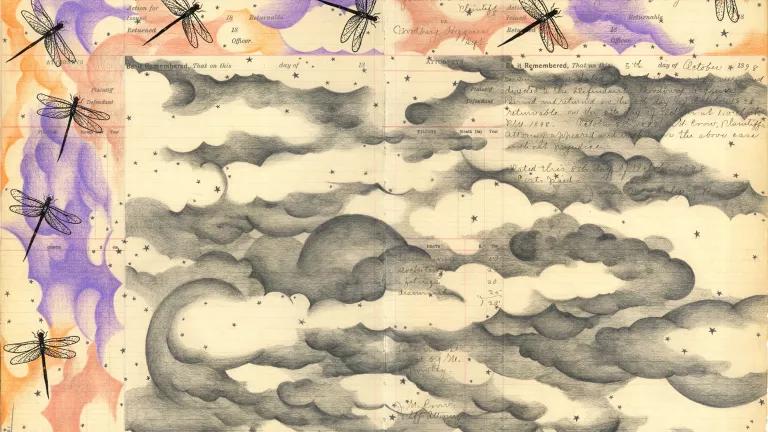

Districts, 2021 by Wade Patton (Oglala Lakota). Micron ink, prismacolor, graphite on an original ledger page from 1898. “The dragonflies not only represent the nine districts in Oglala Lakota County of South Dakota, but represent happiness and purity in my heritage,” says Patton.

In honor of Native American Heritage Month, we asked five Indigenous writers to share original works of environmental poetry that speak directly to future generations. Their poems grapple with grief and loss—from the construction of unnatural borders to the destruction caused by a warming world—while honoring their relationships to the plants, animals, and topography of their ancestral land.

Importantly, many of their pieces also imagine what a world returned to Indigenous leadership could look like. “A call to protect the land is a call to protect our languages, our families, our communities, and our ways of life,” says poet Jake Skeets. “This poem is a letter to myself and the world reminding us of that fact.”

Tanaya Winder

Winder is an author, singer-songwriter, and motivational speaker, whose written works include the poetry collections Words Like Love and Why Storms are Named After People and Bullets Remain Nameless. She comes from an intertribal lineage of Southern Ute, Pyramid Lake Paiute, and Duckwater Shoshone Tribe, where she is an enrolled citizen. She currently lives on Ute, Cheyenne, and Arapaho lands in Colorado.

Stone Mother

I.

I was born in the desert

learned to cherish water

like it was created from tears.

I grew up hearing the legend, the lesson

of the Stone Mother who cried

enough cries to make an entire lake

from sadness. From her, we learned

what must be done and that the sacrifices

you make for your people are sacred.

We are all related

and sometimes it takes

a revolution to be awakened.

You see, the power of a single tear lies in the story.

It’s birthed from feeling and following

the pain as it echoes into the canyon of grieving.

It’s the path you stumble and walk

until you push and claw your way through to acceptance.

For us, stories have always been for lessons.

II.

I remember my grandmother was well versed in dirt,

the way the earth clung to her hands as if it were a part of her.

We come from the earth. So she tended the seeds

as living beings, planted her garden full of foods

traditional to the land and handled them with care.

Every tree, plant, or rock has a spirit, she said “hear it.”

III.

I listen.

When my mother says words are seeds and to be careful

of the words you say, I pray. For I know each seed

carries a story.

My mother taught me that water is the source

of all living things and to honor life like the circle

we sit in for ceremony. From the doorway in

to the doorway out, life is about all our relations.

IV.

Before I was born, they tried to silence us,

pierced our tongues with needles then taught

our then-girl-grandmothers how to sew like machines.

You see, colonialism has always been

about them not seeing us as human but as object,

a thing. Conquest meant they saw our bodies as land,

full of resources waiting to be extracted and exploited.

Our land was stolen.

Our language. Our grandmothers, grandfathers, fathers, sisters, mothers, brothers, daughters, sons, children, nieces, nephews, aunts, uncles, and ancestors.

Our Mother Earth holds our histories in her dirt.

But today, she burns not in the traditional ways once taught,

controlled and deliberate. Today she burns desperate,

for all to resist fossil fuels, the drilling, and the black snake named

greed that swallows everything.

V.

When you lose something, you hope it will be found.

When something is stolen, you want it returned.

We’ve had our land stolen and we’re losing it again

unless we all take action for the climate to change.

VI.

Land back is a demand, a stand

against the Age of Exploration and Extraction,

a call for the Time of Reconciliation, the Now of Restoration

Land back is an understanding

that tomorrow isn’t promised, but today we can return

the power to the earth and her stewards.

And those who wish to stand with us

must take action beyond the performative

where Indigenous consulting isn’t just a costume of free

and informed consent, where consulting with tribal nations

isn’t just a box one checks without due diligence, where co-management isn’t co-opted

just for the optics of equity, diversity, and justice.

Stand with us as accomplices.

Follow our lead for we have always been well versed in survival.

We were shaped by fire, made from lightning and

dirt-covered hands that know when to ignite healing.

Now is the time. Let us not drown in Mother Earth’s tears.

Mother Earth has a spirit and she’s asking us to listen.

Jake Skeets

Skeets is a poet and teaches at Diné College in Tsaile, Arizona, located within the Navajo Nation. His first book is Eyes Bottle Dark with a Mouthful of Flowers, a winner of the 2018 National Poetry Series.

K.yah | Saad: Toward an Open Poetics

In this essay, I will

— locate the land’s locution

— shimmer inside a word’s mineral

— make my home sentence twine

— turn possessives into antiquated vocabulary

In this essay, I will

leave this place —

the desert is no sea its glimmer only black rock

knelt at the skycase

a chimney of sun tar and asphalt

beneath the rake and roll of cactus and canyon seed

spring dew taunts tarantula and scorpion

parched in a midday temperature high

for springtime or late fall

In this essay,

the desert is a love letter

there is no sea

a desert undertow is thirst

its riptide a dust devil

fairy wind on the San Juan basin

the light casts its name in tarmac

swarm and memory

In this something other than essay

somewhere there is a fire

about to happen or is happening or has happened

In this I will

this is the high desert, i.e., a place with light

so much of it we forgot how to look

In this desert, I will

light the hardened meadow with a technology so ancient we call it language.

This is what I mean:

the field steps pink onto a hairline road

the sun washed on morning needle and wrestled sap

it was an early frost followed by late heat

there are no rules or boundaries out here

the trees at the tree line are only a border

if we say it is—the same goes for river or alcove

If the lights go off any one moment, would we fear

the darkness? In it, we can’t see the cornfields

empty of corn or weeds growing in the abandoned mine.

In this darkness, I will

write another love letter to winter and call it by its real name

language, after all, is the only sound it can hear

I will say I am from here, this desert, a home

I refuse to let a border town be my name

Where are you from, they’ll ask

Háadę́ę́’shą’ naniná?

Here, I’ll say. Everywhere.

Amber McCrary

McCrary is a Diné poet, zinester, and feminist. She is Red House clan born for Mexican people clan. Originally from Shonto, Arizona, and raised in Flagstaff, McCrary received her MFA in creative writing with an emphasis in poetry from Mills College and is now the owner and founder of Abalone Mountain Press, which is dedicated to publishing Indigenous voices. She currently resides on Akimel O'odham land.

Self-Portrait as a Saguaro

Sometimes I feel like you

a flowering hosh, has:an, saguaro

breathing in the rocky sand

A bright, boiling star, eyes, my waxy, sprinkled skin

I look at you and I can feel the prickled

toothpicks stand on my skin

just like when I see the hosh of my eye

I feel like you before the monsoons

my ribs dry from the heat

ready for the rain

& the new year

However, this year is particularly funny

but what does this tall saguaro know?

the rain is solemn

the rain does not repeat

like it used to

I see relatives pick off

my bearable fruit

for years longer than something called a nation state

whatever that is

Sometimes I see you leading

me to other hosh older

than the state of Arizona

standing taller than the

politicians looking like overwatered prickly pear

with pricks spilling out of their mouths

poking and bleeding out

letters with no song

Sometimes I feel like you

seeing freeways being built

over my relatives and friends

feeling the rivers dry in my spine

My belly unfull

In the heat

The magnificent heat

under my weight

I am protected beyond the laws

by something stronger

something laws cannot govern

When I see you

my belly is full

& the rain clouds appear

bustling, dripping, rested

Please let it keep raining

My spine crackles in between love and loss

of language and land

the cars spit grief in the name of sublime song

A terror to us, a barrier between my skin and song

We can't hear it anymore

only the sound of wheels whizzing and whirring

all in the name of a construct of the mind

the loveless of the sands

it is raw in your belly

it is raw in their language

it is raw in a bleeding mind

Please do not let my belly disappear

Kinsale Hueston

Hueston is a Diné poet, performer, and junior at Yale University studying the intersections of cultural (re)vitalization movements, Indigenous poetry, and Indigenous feminism. Usually based on occupied Tongva Lands (Los Angeles), she works with Native youth in storytelling and mental health programming, edits Changing Wxman Collective, and can often be found penning love poems to the high desert. She currently lives on occupied Quinnipiac Land in New Haven, Connecticut.

after Sacred Water

I.

we inherit:

every gathering pool a blessing

formed by careful hands each monsoon

a heartbeat turquoise vein

the sound of underwater

brimmed with mosses

here laps the quiet tide of love

II.

in the summers we would flock to my great-aunt’s

swimming hole down the canyon

dizzy from the jumbled journey in a truck bed

poke at the tadpoles squirming in the red clay

my mother watched from orchard shade

she had been down here many years before

with her sisters her brothers

picking apples, following the bend

of the river leading the goats to the wayside to drink

now the water is too polluted

with cow manure uranium

we trace the mud with our eyes

watch the petroglyphs stretch in the shadows

miss the feeling of the sun wicking river from our skin

III.

in 1956/ the glen canyon dam began construction/ with an explosion/

was hit with a demolition blast keyed/ by the push of a button/

in the oval office/ the bottom of the canyon/ dotted by navajo/

ute/ paiute footprints/

still cooling/ the explosion/ a scar in the earth still aching

with uranium mines/ yellowcake/ yellow corn/ tumbled

in the runoff/ what do you call ancestral homestead/

stopped like a kitchen sink/ the water/ of your people

redirected to ranches/ fatten cattle that render the san juan undrinkable/

quench the white men in bars that don’t admit ndns/ water

and mineral/ packed into bombshells/ how do you drown

by your own artery/ today

the lake has never been shallower/ a drought

of its own becoming/ not even time to weep/ before the crossing/

before the fleeing/ marina of familiar fossils/ zebra mussels

scour the bones of old adobe/ stilled

beneath the surface/ the ancient sun rendered closer/

every day/ as the ranchers lament the withering/ the tourists

sticky with sun/ dock their houseboats/ the people who have known

this land/ see the slickrock

still emerging

IV.

in the third world, coyote took the water monster’s baby

so the water monster decided to make it rain endlessly

the water rose and flooded and choked the peaks

of sacred mountains

and the beings that lived there

did not know where to escape the flood

what saved the world was a reed curling

into the sky a way to climb out into the fourth world

an offering by First Man beloved by the gods

the one from which we all were formed

there are things that remain stolen that holy people

weep for and others look to us with upturned hands

ask where the reeds come from flee to the highest peaks

dream of another world they can scurry into

through a wound in the sky

we have no answer for them we have known this the entire time

tell our stories go to the water

tend this land

and remember

Edyka Chilomé

Chilomé is a queer, Indigenous, mestiza cultural worker, writer, poet, and child of migrant activists from the occupied lands of the Zacateco (Mexico) as well as Lenca (El Salvador) people. She was raised in migrant justice movements grounded in the tradition of spiritual activism and was deeply formed by the works of Black feminist writers as a reindigenizing woman in diaspora. Chilomé is the author of two collections of poetry: She Speaks Poetry and El Poemario del Colibrí: The Humming-bird Poems. She currently lives east of the Arkikosa River (North Texas) in a 200-square-foot tiny house with her animal companion.

The Archive of Our Relation

I admit, the mourning is constant

the names, the words, the whispers

colors and textures that were lost,

persecuted, poisoned, disinherited,

extracted, cut down, shaved, kidnapped,

unclaimed, and forgotten. An endless war

I too report, my silence has not saved me

yet running water calls spirits

hidden in me carefully

waiting for me to quiet the mind

so they may wake me right on time

to witness the great expanse

a dance so tender

it gently wakes the sun

In gratitude the sun rises

offers its power

so that we may see

all that has been done

all that is yet to come

In humility and courage

I rise, offer my power

so that I may see

all that has been done

and you who has yet to become

Tumal sinú

may the sun always shine on you

a prayer weaved by

the most precious parts of me

a breath

the most potent offering

to our becoming

I report, the water, the earth, the seeds

and the grace of a dancing sky

remain a pure reflection

the wealth of our inheritance

the heart of our connection

the archive of our relation

if we so choose to co-conspire

to re-member

Agua es vida, Water is life

we are the water and

remembering has offered us

our lives, love letters bloomed beautiful

in anticipation of you

travel guides to the

ancient futures that are due

living memory of

gestation and labor

humble testimonies

conspired in your favor

You see, more than hope

we hold a deep knowing

all creation moves in circle

all that was once dead is reborn

the breaking of the seed

a necessary violence

forgiveness a necessary blooming

resistance a necessary rooting

rebuilding a defining act of courage

letting go a radical act of love

I too agree with trees

I do not shy away from the darkness

Nor do I fear the wind

I remember the water

and take root in the memory of you

the living archive of relation

a sweet and sacred confirmation

that we are still alive.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Deb Haaland Is the Interior Secretary Our Country Needs

A Trailblazer for Tribal Sovereignty

They’re Spreading the Joy of Birding—and Making It More Inclusive