“Forever Chemicals” Called PFAS Show Up in Your Food, Clothes, and Home

These toxic chemicals are so common in consumer products and manufacturing that they’re everywhere—including inside our bodies.

Whitney Ulven/Offset

Nonstick cookware, grease-resistant food packaging, and waterproof clothing are all products that make our daily lives less messy, but that convenience comes at a cost.

A class of manmade chemicals known as PFAS—which stands for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances—is part of what makes these consumer goods water-, stain-, and grease-resistant. PFAS are also toxic at extremely low levels (i.e. parts per quadrillion), posing significant risks to our health. And if you’re wondering why they’re called “forever chemicals,” it’s because they are nearly indestructible.

Unfortunately, PFAS are almost impossible to avoid. They are found in our homes, our offices, our supermarkets—practically everywhere.

Erik D. Olson, NRDC’s senior strategic director of health and food, says PFAS are dangerous for three crucial reasons. “First, the structure of PFAS means they resist breakdown in the environment and in our bodies. Second, they move relatively quickly through the environment, making their contamination hard to contain. Third, for some PFAS, even extremely low levels of exposure can negatively impact our health.”

What’s worse, manufacturers don’t have to disclose to consumers that they’re using them and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) doesn’t regulate or test for most PFAS chemicals. So here’s what you should know and tips on how to protect yourself.

What Are the Health Effects of PFAS?

PFAS have now been linked to a wide range of health risks in both human and animal studies—including cancer (kidney and testicular), hormone disruption, liver and thyroid problems, interference with vaccine effectiveness, reproductive harm, and abnormal fetal development.

Many of these problems, including kidney cancer and thyroid disease, turned up in the C8 studies, which monitored the health of about 69,000 people in West Virginia who were exposed to certain PFAS in their drinking water. Key adverse effects of some PFAS were known by chemical industry scientists decades ago, but were not disclosed to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or the public. For example, EPA issued a multimillion-dollar fine to manufacturer DuPont because of the company’s “multiple failures to report information to EPA about substantial risk of injury to human health or the environment” from the PFAS perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA or C8). Now, scores of independent studies show PFAS can be toxic to adults and especially children, whose developing bodies are more vulnerable. Some PFAS have even been known to build up in a child before birth. Alarmingly, PFAS were detected in the breast milk, umbilical cord blood, or bloodstreams of 98 percent of participants in a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

PFAS in Clothes

Whether found in a raincoat or a pair of yoga pants, PFAS are used widely in our clothing, shoes, and accessories. These chemicals also cause pollution at every stage of production. At the PFAS chemical manufacturing facilities and garment factories, they often contaminate the air, water, and soil of the surrounding environment.

Products coated in PFAS can also expose consumers directly during use. And PFAS-treated apparel that is washed and eventually dumped in landfills or incinerated leaks “forever chemicals” into the environment at the end of its life cycle too. Pollution generated far away also circles the globe, for example, through ocean waves or rain, with wide-reaching impacts.

“The functionality that PFAS provides—a more stain-resistant coat or more breathable yet water-resistant gym shorts—is not necessary and certainly not worth the health risks,” says Sujatha Bergen, a coauthor of a recent NRDC report titled Going Out of Fashion: U.S. Apparel Manufacturers Must Eliminate PFAS “Forever Chemicals” from Their Supply Chains. “We lived just fine without these chemicals before, and brands could phase them out quickly if they chose to.”

Unfortunately, there are no laws in the United States requiring manufacturers to warn consumers that an item was made with PFAS (though a new bill passed in California, AB 1817, phases out the chemicals in clothing and textiles sold in that state). Generally, you’re better off assuming that something does contain PFAS, particularly if you find keywords like “waterproof,” “stain-repellent,” or “dirt-repellant” on the tag.

In response to pressure from both consumers and groups like NRDC, a number of apparel brands are taking action. Levi Strauss & Co., Victoria's Secret, and Deckers Brands have already removed PFAS from their merchandise. Other major brands, like Ralph Lauren and Patagonia Inc., have set time-bound commitments to do the same. But they are still in the minority.

Take Action

- The best way to find out whether your item of clothing is PFAS-free is to check the brand’s website to see if it has announced that it has eliminated PFAS from its clothing or labeled clothing lines as PFAS-free. If no information is available, contact customer service to ask directly. Don’t be fooled by labels or promises that a product is “PFOA-free” or “PFOS-free,” since those two particular PFAS chemicals have already been eliminated from U.S. production and there are many other PFAS-containing substitutes in widespread use.

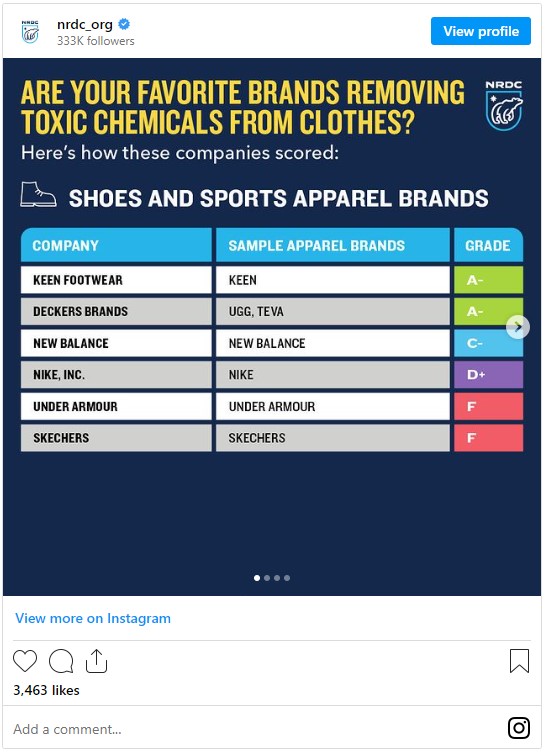

- Review the brands covered on NRDC’s PFAS apparel scorecard. You can also check out PFAS Central, a project of the Green Science Policy Institute, which offers a helpful list of products and brands that state they offer PFAS-free outdoor gear, apparel, and other products.

PFAS in Water

Water systems in 50 states have been contaminated with PFAS, according to data collected by the Environmental Working Group and Northeastern University. The contamination comes from several sources—like the industrial (and still mostly legal) dumping of PFAS directly into rivers, lakes, and streams, or the seeping of PFAS into groundwater from trash in our landfills and from burning PFAS containing products and waste in incinerators.

Now, it’s estimated that more than 200 million Americans could have PFAS in their drinking water at levels that could impact health. And this pollution is often even more intense in already overburdened environmental justice communities, according to the NRDC report Dirty Water.

The EPA did recently propose setting limits on six PFAS chemicals that are regularly found in drinking water. The problem is that there are thousands of PFAS chemicals in use, and the agency does not test for a vast majority of them, making its approach woefully inadequate. In fact, when NRDC partnered with impacted communities to conduct more comprehensive testing of drinking water samples from across the country, it found 26 unique PFAS, including a dozen that the EPA would have missed. The most widely detected chemical—which is among those not covered by the EPA’s current testing methods—was an ultrashort-chain PFAS called perfluoropropionic acid (PFPrA).

Brian Maranan Pineda for NRDC

Take Action

- There are steps you can take to protect yourself. Start by asking your water provider for data on PFAS testing in your area. If there isn’t any data, ask the provider and your state to start monitoring for a wider range of these chemicals. If there is contamination, ask your state and water provider to install treatments to remove PFAS from your water. This is only currently legally required for certain PFAS in certain states, but a provider may still do it voluntarily.

- In the meantime, certain home water filters can help reduce contamination levels. A recent Duke University and North Carolina State University study found that reverse osmosis filters installed at the point of use were most effective at removing PFAS. The effectiveness of activated carbon filters, found in some pitchers or installed in refrigerator doors, was less predictably effective.

- Note that boiling your water does not rid it of PFAS and can actually make its concentration higher.

PFAS in Food

PFAS has infiltrated our food system too. These chemicals are frequently used to make packaging like pizza boxes grease-resistant or to make pans nonstick. Thanks to a petition from NRDC and our partners, the U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) banned three PFAS chemicals from use in food packaging in early 2016, but hundreds of their chemical cousins are still widely used. NRDC and our partners have since helped pass laws in California and New York that ban PFAS in paper-based food packaging, starting in 2023. Several other states have also taken action, but use may persist elsewhere.

Idris Soloman for NRDC

Food can also be contaminated with PFAS via the soil, water, and air where it’s grown. In a 2018 study, the FDA assessed produce grown near a PFAS manufacturing plant. Of the 20 samples taken, 16 were found to contain PFAS. Studies have also detected PFAS in fish and shellfish sold for human consumption in the United States.

Take Action

- You can avoid the most obvious offenders by replacing nonstick pans with stainless steel, cast-iron, glass, or ceramic alternatives.

- Also, don’t heat up food that’s wrapped in grease-resistant packaging. And make popcorn on the stovetop instead of in PFAS-treated microwave bags.

- Keep in mind that compostable packaging that’s BPI-certified does not contain PFAS.

PFAS Around the House

Home goods aren’t spared from PFAS contamination, either. Everything from your mattress pad and umbrella to your cosmetics and dental floss may be treated with PFAS, leaving families vulnerable. Children in particular, who are more likely to put PFAS-treated products into their mouths, are at higher risk. Similar to the designers of clothing and food packaging, home goods manufacturers are not required to inform consumers of the presence of PFAS in their products.

Take Action

- The simplest way to reduce your exposure to these toxic chemicals is to opt against buying any furniture, rugs, and bedding that are labeled as being water- or stain-repellent. Those treatments are practically guaranteed to contain PFAS. If you’re wondering about a potential purchase, check the manufacturer’s website and labels for whether its products are PFAS-free; some manufacturers of rugs and carpets have eliminated these chemicals.

The Continued Threat of Newer-Generation PFAS

In recent years, manufacturers have started to use shorter-chain PFAS because they move more quickly through the human body than longer-chain ones, such as the three chemicals the FDA banned from food packaging. That may sound like a positive step, but it hasn’t made a real difference.

“Companies will phase out a longer-chain PFAS,” explains NRDC staff scientist Anna Reade, “then replace it with a regrettable substitution—a chemical that’s slightly different but likely to trigger the same health problems as what it’s replacing.” There’s evidence this is already happening. According to reports by the EPA, two newer-generation, shorter-chain PFAS, GenX and PFBS, were shown to be linked to similar health effects as the PFAS they replaced (PFOA and perfluorooctane sulfonate, or PFOS, respectively). That’s why NRDC strongly supports regulating PFAS as a class. Indeed, scientists, including those at California’s Safer Consumer Products program, have called for the same. NRDC will also continue to demand stricter regulations as well as more comprehensive testing and transparency surrounding all PFAS included in consumer goods.

Policy Progress Against PFAS

In good news, there have been a series of important victories in the battle to curb the use of PFAS. This included the 2002 phaseout of U.S. production of PFOS as well as the 2015 phaseout of domestically produced PFOA, which was used in the making of Teflon pans and identified as a possible carcinogen in humans.

And, in addition to the critical FDA decision to ban those three PFAS chemicals from food packaging, we’ve seen promising local legislative action. Multiple states, including New Hampshire and New Jersey, established tap water standards for certain PFAS. California and New York also joined other states in banning PFAS from plant-based food packaging and in firefighting foam and textiles. In the private sector, companies like Home Depot and Lowe’s have chosen to eliminate PFAS in their carpets and rugs, and a wave of clothing brands, including Patagonia, are making public commitments to remove PFAS from their entire supply chains, signaling the potential for new market norms to take hold.

The Biden administration has also taken promising, but not yet sufficient, steps to begin tackling PFAS contamination. In 2021, the EPA released its PFAS Strategic Roadmap, which laid out the agency’s intentions to increase research into health impacts and put more pressure on PFAS manufacturers to limit pollution. And earlier this year, the agency proposed setting limits on the amounts of six PFAS chemicals in drinking water. But the administration’s response still fails to meet the scale of the crisis with more comprehensive monitoring, definitive regulations, or wide-scale cleanup efforts.

The reality is, we need to take action on the full class of these toxic “forever chemicals” to clean them up, phase them out, and then ban them for good.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

The Smart Seafood and Sustainable Fish Buying Guide

Three Ways We Can Make Schools Healthier This Year

Neonicotinoids 101: The Effects on Humans and Bees