How to Find Out If Your Home Has Lead Service Lines

A step-by-step guide to help you check for lead pipes—and the questions to ask of your local water utility.

A construction crew working around a ditch dug during the replacement of a lead service line outside homes in the West Roseland neighborhood of Chicago, June 2023

Vanessa Bly Photography for NRDC

Throughout the country, tens of millions of people are at risk of drinking tap water contaminated by lead, a neurotoxin that’s particularly harmful to developing young brains. The cause? In many cities, the pipes that carry water from the street into homes are made of this dangerous metal, essentially acting like lead straws. Although most of our household plumbing contains some amount of the material—whether in faucets, fittings, or lead solder—it’s these service lines that present the largest source of lead in drinking water today.

This is a massive public health crisis, as health experts agree that there is no safe level of lead exposure. The risk is nationwide and affects communities of every stripe, but it remains particularly high in low-income communities and communities of color, as evidenced by a number of high-profile drinking water crises in cities like Flint, Michigan, and Newark, New Jersey.

Given the scale of the problem—more than 9 million lead service lines deliver water to homes across the country—pressure is mounting for lawmakers, municipalities, and water suppliers to speed up the work of pulling lead pipes out of the ground and replacing them with new nontoxic pipes. In the meantime, you can take steps to find out whether your home is connected to a lead service line and, if it is, what to do next.

Water service lines: These are the underground pipes (measuring about the diameter of a garden hose) that connect water mains—the large pipes that carry the public water supply and typically run under or parallel to the street—to homes and other properties. They were commonly made of lead from the late 1800s through much of the 20th century. In 1986, as pressure mounted to address the clear health risks, Congress enacted an amendment to the Safe Water Drinking Act, officially prohibiting the installation of new lead service lines and other plumbing. The ban took effect in 1986 (with many states waiting until 1988 to enforce it), but the legislation was far from comprehensive: It didn’t require existing lead service lines to be replaced. City, state, and federal officials are now working to reverse this injustice, including through funding administered under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Request information directly from your water system

Reach out to your public water system—contact information can be found via your city or county’s website—and ask what materials make up your home’s water service line. Keep in mind that some water systems may consider lead goosenecks or pigtails (see figure below) to be separate from the rest of the service line, so you should ask specifically if these were ever used and during which years they were common.

Unfortunately, many water systems don’t keep complete records on which materials were used and where, making the process of finding the remaining lead lines a significant hurdle in replacing them. Historical records kept by municipalities may be similarly spotty. Some communities never used lead lines at all. Others, like Chicago, installed lead service lines until the ban took effect in the mid-1980s.

If your water system representative says you have a lead service line, skip to the final step below. If you are told the service line contains no lead or is made with another material, ask for written proof. Even if the water system has records indicating a non-lead pipe at your house, it will give you peace of mind to make a few more basic checks to verify the information.

If you don’t get a clear answer on whether your house has lead pipes, compile a brief history of your house

Look for these key dates:

- The year your house was built

- The year your house or property first got water service

- The year your house was renovated or a new house was built on a property that already had water service

Tax records, real estate listings, and building permits are all good sources for this information. The year a house first received water service is typically the same year it was built, but some communities may have used private wells prior to connecting to a public water system. If this information exists, previous homeowners or the water utility can likely provide it. (Note: Private wells themselves can pose a problem, since groundwater can be corrosive and leach lead from indoor plumbing or from submersible pumps.)

- If your home was built after 1988 with a new water connection, you can be confident that you do not have a lead service line.

- If your house or property first got water service before 1988, there is a chance you may have a lead service line, even if your home was remodeled or replaced later, but more investigation is necessary (see below).

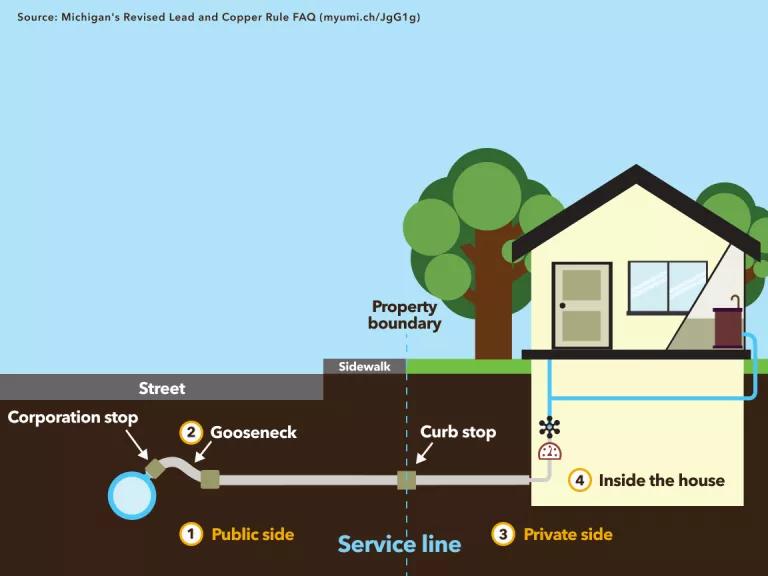

A lead service line can have up to four sections: the public side, gooseneck, private side, and inside the house.

NRDC

Learn the anatomy of a service line

A service line can have up to four distinct portions, as shown in the figure above. Any one portion, or all portions, can be made of lead, but they are also often made of copper, galvanized steel, or plastic.

- The section from the water main in the street to the curb stop near the property line is often considered the “public side” and is typically owned by the city. The corporation stop and the curb stop are both valves that can be used to stop the flow of water to your house.

- In some cases, there is a gooseneck or pigtail (typically a pipe of two feet or less) that bends to connect the service line to the water main. It’s often made of lead.

- The section from the curb stop to the house typically runs on private property and is sometimes called the “private side.” Sometimes water utilities will assert that this portion of the service line is privately owned (and therefore not their responsibility to replace), but the ownership of the service line in many cities is unclear and requires careful investigation.

- The only portion of a service line that can be identified without digging into the ground is the short piece of pipe inside your home that runs to the meter or the main shutoff valve. This section can be made of a different material than the buried portions of the service line.

Check the service line where it enters your home

The next step is to check for yourself. You’ll want to find where the service line enters your home—typically in the basement or crawl space, just prior to the shutoff valve. The water meter may be in the same location, but in some areas, the water meters are outside the home. The photo below (left) depicts a typical configuration for service lines and meters, although the orientation of the pipes in your home may differ.

Locate where the service line comes into your house near the main shutoff valve. Look for the test area between the wall or the floor and the shutoff valve, shown circled in the picture on the left. In some locations, the service line may not be visible at all, like in the photo on the right. In that case, you have to rely on water utility records or dig it up to confirm the material.

If you can see the test area, gently scratch the surface of the pipe with a coin. If the pipe is soft and easily scraped, silver in color, and if a magnet doesn’t stick, it is lead. It may have a bulb in the pipe near the shutoff valve that looks like a snake that swallowed an egg.

If it’s not lead, here are some ways to identify the material.

- If a magnet sticks, this portion of the service line is galvanized steel.

- If it is copper-colored and a magnet doesn’t stick, this portion of the service line is copper.

- If the pipe is white or gray and the piping is joined with a clamp, screw, or glue, this portion of the service line is plastic.

Keep in mind that there are some limitations to this DIY work: When the pipe is painted or wrapped, its material may not be easily identifiable. And sometimes the shutoff valve is actually under the floor or behind a wall and no portion of the service line is visible at all inside the house.

The left photo shows a typical configuration for service lines and meters, although the orientation of the pipes may be different depending on the home; the circled area indicates the test area between the wall or the floor and the shutoff valve. The right photo shows instances where the service line may not be visible at all.

Detroit Water and Sewerage Department

; 2)Detroit Water and Sewerage Department

If you’re still not sure, you may need to keep digging

If you didn’t find a lead pipe where water comes into your home, there’s still a possibility that you have one buried between your home and the water main. If you live in an older house and you see freshly patched flooring around your service line, it’s possible the service line was recently replaced. There’s always a chance that it was only replaced inside the house, making it important to check with the water utility or to look back at the building permits and records for your house.

The most reliable way to identify the buried pipe material is by working with your water system to dig up and reveal the service line’s public and private sides at the curb stop. Many different terms have been used for this process, including excavation, potholing, and hydrovacing. Usually, it’s not necessary to dig up the whole service line to figure out what it’s made of; small pits can be dug up or hydrovaced at key locations to determine the pipe’s material.

If a lead service line was partially replaced on the public side only at a prior time, the connection of the old lead service line to the new material can be as far as 2 feet away from the curb stop on the private side. Partial lead service line replacement (meaning that a utility replaces only the “public” side of a lead pipe and leaves the “private” side of the lead service line in place) is a common—and dangerous—water industry practice.

If you do have lead pipes, take these safety steps

If you’ve confirmed that you have a lead service line, then it’s important that you protect yourself and your family from further lead exposure, particularly if you have young children or are pregnant (or may become so).

- Take a picture of your service line and send it to your water system so the agency can verify your results and update its records as necessary.

- Test your home’s water to determine the degree of lead contamination. In some cities, the water system will send water testing kits to residents directly. You may also be able to request a city official to come out and conduct this test.

- Keep in mind that lead levels can vary wildly from the same faucet. These changes can stem from nearby construction that loosens lead particles, or even something as simple as recent water use, among other factors. In other words, a single lead test showing low or no lead is present isn’t an all clear sign, as lead levels may be higher on another day. Of course, if a test does find high lead levels, that’s a clear sign of a problem and merits taking protective action (such as using a water filter).

- Install a water filter that’s certified to remove lead by either the Water Quality Association or NSF (labeled as meeting NSF/ANSI Standard 53 for lead removal). See this guide on how to pick and operate a filter, and this one for a list of filters that reduce lead levels.

- Use only cold water for drinking and cooking, and never run warm or hot water through your filter as that will damage its ability to remove lead.

- When using water for drinking or cooking, run the tap for five minutes or more to flush the water that was sitting in the pipes. (You can always collect that water for a task like watering plants or for washing.)

- Parents should have their children tested for lead exposure by a doctor.

- If lead contamination is present, use a certified filter for drinking and cooking, and particularly for preparing formula for infants, until the lead line is replaced. Generally, NRDC recommends a certified filter rather than bottled water unless there are issues beyond lead in your water (such as violations, microbial contamination, or frequent boil water alerts from your water system that indicate other underlying problems).

Request that your home be added to the water system’s lead service line replacement program and ask what programs the agency offers to do this for free or at a reduced cost. Remember that a full (not a partial) service line replacement is the only solution to permanently address lead contamination and protect your health.

Elin Betanzo, principal of Safe Water Engineering LLC, contributed to this story.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Up to 22 million people in the U.S. are drinking from taps poisoned with lead.

Tell the EPA to finalize strong standards for safe drinking water!

How to Protect Yourself from Lead-Contaminated Water

America’s Failing Drinking Water System

How Exactly Does Lead Exposure Harm the Brain?