These Energy Efficiency Advocates Give Home Comforts a New Look

The Association for Energy Affordability is helping to keep low-income housing cool in the summer, warm in the winter, and good for the pocketbook and our climate, all at the same time.

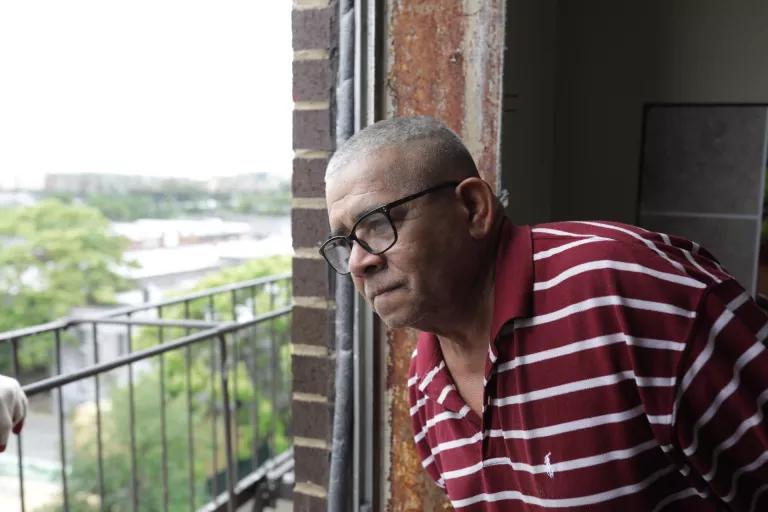

Association for Energy Affordability's Francis Rodriguez

All images by Natalie Keyssar for NRDC

When Francis Rodriguez tours homes in the South Bronx, he pays special attention to the features that should keep a place cool in the summer and warm in the winter, with enough hot water to go around, and at rates that won’t break the bank. After all, says Rodriguez, director of weatherization at the nonprofit Association for Energy Affordability (AEA), “we go to many houses where homeowners are choosing between fuel and medicine.”

Not only can out-of-date heating systems factor heavily in the cost of a resident’s monthly utility bills but so can old faucets and refrigerators, drafty windows, and incandescent light bulbs. By conducting energy audits to identify potential savings through infrastructure tweaks in homes in the Bronx and Queens, Rodriguez and his colleagues at the New York City–headquartered AEA are boosting housing sustainability and affordability, with a focus on low-income families of color.

A direct services subgrantee and technical services provider for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), AEA has conducted more than 1,670 energy audits since 2007 and retrofits some 400 to 500 housing units annually. A decade ago, AEA expanded its work to California and Chicago, where it also focuses on developing new affordable, energy-efficient, multifamily housing.

Rodriguez has worked in the weatherization field since 1994, when he got a job at another nonprofit in order to help pay for his tuition at Lehman College, where he studied computer information systems. He’s been with AEA for the past 21 years. Rodriguez knows the neighborhoods he works in, and the struggles their residents face, intimately: When he and his three brothers first arrived in New York from the Dominican Republic as teens, they settled in the East Bronx with their father (their mother came five years later).

“In those years, my family lived in a building with heating issues. We were paying rent yet having to deal with heating imbalances—that situation of uneven heating, weathering days where you have no heat in your apartment because the boiler isn’t working properly,” he says. “So I definitely know what it’s like.”

At AEA, Rodriguez oversees installation work in exterior and interior insulation, windows, lighting, and heating and cooling. The work begins with Rodriguez and his crew analyzing a house or apartment, looking for opportunities to increase health and safety or improve savings. Many of the crew members are hired through the Pathways Out of Poverty program, a federally funded workforce development grant, which supports green jobs for members of the low-income communities served through WAP, or through state-, city-, or utility-funded programs for income-eligible families and landlords.

Rodriguez credits his own training through the program for his early advancement in the industry and stresses to those coming behind him that continuing education made his career possible. And the AEA team expects these types of job-training initiatives to grow over the coming years, especially if boosted by federal infrastructure investments through President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda. In a recent op-ed, the organization’s director of West Coast operations, Andrew Brooks, noted that the economic payoff from building, weatherizing, and upgrading two million affordable homes in cities across the country, as Biden has called for, “will be felt for generations to come.”

The mission of upgrading homes and reducing energy bills for low-income households is especially critical given that the proportion of earnings they spend on energy is, on average, more than three times the proportion paid by average households. As a result, says Rodriguez, “many times, these are buildings where they just can’t afford to do the improvements,” like adding more efficient showerheads or LED light bulbs. It is part of AEA’s mission to help low-income residents overcome these barriers to basic upgrades. “In one- to four-family-unit houses, if the owner qualifies, whatever work we do is free,” he says. “They don’t have to pay.”

It’s not just renters who struggle to keep up with home improvement costs. “On the multifamily side, even though these are landlords, they’re often developed and managed by a nonprofit that’s just surviving, in keeping up with building expenses,” Rodriguez points out. “In helping them reduce their energy bills and make the proper improvements to the building, we are making sure tenants don’t go suffering for lack of heat and hot water.”

The landlords who are helped must agree not to raise rents.

“In New York City, landlords are allowed to pass the cost of major capital improvements on to tenants, who end up paying higher rent,” Rodriguez says. In turn, these investments—which may have been intended to foster energy affordability and climate resilience—could lead to green gentrification and displacement. “One of the requirements of the weatherization program is that owners cannot request a rent increase for the work we do.” And that protects tenants.

Breathing Easier

AEA also seeks to improve respiratory health through the upgrades it provides. Like many low-income communities of color, the South Bronx, where the population is 56 percent Latino and 38 percent Black, has a long history of environmental racism. Communities are surrounded by an inordinate amount of polluting industries, major arterial highways, and diesel truck traffic, along with waste transfer stations (hubs where the sanitation department transfers waste coming in from all around the city onto trucks for shipment to landfills, incinerators, and recycling facilities outside of New York), which contribute further to air and noise pollution. Partly as a result of living with these environmental hazards, the South Bronx has a notoriously high prevalence of asthma.

“We started addressing air quality about four to five years ago, making sure we are adding enough ventilation to units to avoid mold and mildew and provide better indoor air quality,” says Rodriguez. “[That’s] especially important in areas of the Bronx where there’s a lot of through truck movement because of all the factories and warehouses.”

In order to help cut down on pollution exposure, AEA recently began introducing electric-powered heat pumps that provide both heating and cooling to many of the buildings it serves, replacing those that run on dirtier energy forms. “A lot of the buildings we worked on were using heavy oils, No. 6 and No. 4, for heating and hot water, which produce heavier pollution. Electric is more predictable, offering better performance,” Rodriguez says.

The upgrades are also better for the climate since heating and cooling account for almost half of the energy use in a typical home in the United States. “Society is now realizing something that we at AEA realized a long time ago: When you reduce the cost of energy, you’re very much responding to climate change,” says David Hepinstall, who cofounded AEA in 1992. At 81 years old, he still runs the organization and sits on policy advisory bodies at the city, state, and federal levels, promoting best practices for energy consumption reduction in multifamily housing. He maintains that the work is more critical now than ever. “The reality is we have a society that has had a lot of barriers to doing energy efficiency work in low-income communities, due to a lack of adequate resources. The federal weatherization program has made a real difference,” he says.

Residents like Emiliana Ocampo, a 50-year-old home caregiver for the elderly, are benefiting directly. On a recent day, Rodriguez was overseeing installation of high-performance, energy-efficient windows at Ocampo’s building, a 96-unit, low-income building in the South Bronx. (Windows like these, Rodriguez notes, typically reduce utility bills by at least 10 percent.)

Watching him and his workers closely was Ocampo’s brother, Raul Alberto Ocampo Ariza, who was house-sitting while his sister was at work and while her 18-year-old son was busy with his homework. The brother and sister immigrated from Colombia in 1997, and Ocampo has lived in this Bronx residence for the past three years, sharing her one-bedroom apartment with her son.

“I’m not currently working, so if she needs anything, I come and help her out,” Ariza says. “There were about 12 workers. It took them about four hours to take out the old windows, put in the new windows, and clean everything up. The new windows are nicer, and my sister thinks they are really pretty. She’s a single mother and doesn’t earn a lot of money. If it saves money, it will help her.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

After Decades, Tenants Are Still Fighting NYC Public Housing for Speedy Mold Relief

A Catalyst for the Midwest’s Clean Energy Transition

NRDC's Commitment to Green Starts with Its Offices