A Trailblazer for Tribal Sovereignty

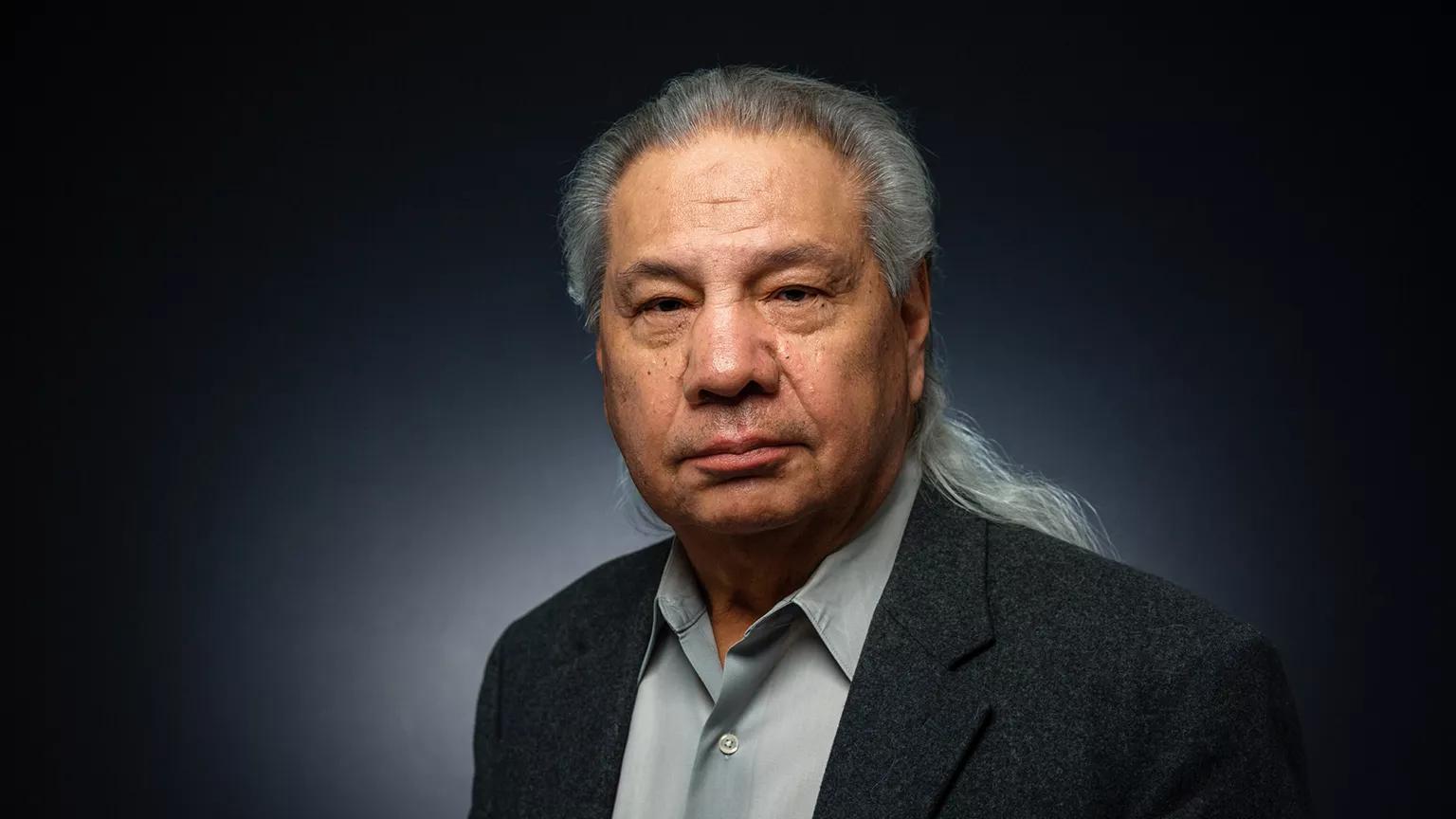

NRDC Board member John Echohawk, a member of the Pawnee Nation, has devoted his career to asserting the legal and civil rights of Native Americans.

NRDC Trustee John Echohawk

More than 50 years ago, John Echohawk walked across a stage in Albuquerque and received his diploma from the University of New Mexico School of Law as that institution’s first Native American graduate. After the ceremony, the 24-year-old member of the Pawnee Nation hesitated, uncertain of how to plot his next step. There didn’t yet exist a network of Native American lawyers for him to reach out to for professional advice or connections. Most U.S. law schools, in fact, had only just begun enrolling Native American students a few years earlier, thanks mainly to a scholarship program that had been created by the Office of Economic Opportunity as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty.

But Echohawk definitely knew what kind of work he wanted to pursue. In his studies, he had been introduced to the body of jurisprudence known as federal Indian law, the collective term for the specific set of laws and statutes addressing the complex legal relationship between the hundreds of Native American tribes and the U.S. government. Before law school, Echohawk says, “I didn’t know much about it, and the other Native American students didn’t really know much about it. We weren’t really sure our tribal leaders knew about it, either.” He understood that this knowledge gap hurt the tribes, who encountered injustice after injustice at the hands of white colonizers, including dispossession of their lands, their water rights, and their sacred cultural practices. But the more he learned, the more he understood there was a way to fight back. “I thought, That’s what I want to do. That’s what I need to do.”

In 1970, there was no road map for a newly minted lawyer interested in pursuing Native American law as a career. But that didn’t deter Echohawk—and the generations who followed in his footsteps have benefited from the path he blazed. Before the end of that same year, he had cofounded the Native American Rights Fund (NARF), which quickly became the most powerful legal advocacy organization representing tribal interests in the country. Since its inception, NARF has taken on and won hundreds of cases involving tribal sovereignty, treaty rights, natural resource protection, and many other issues that require adjudication within the context of the law. Echohawk has served as its executive director since 1977.

On August 5, the American Bar Association presented Echohawk with the 2023 Thurgood Marshall Award, given each year by the organization to a member of the legal profession who epitomizes the same lifelong commitment to civil liberties, civil rights, and human rights as the legendary Supreme Court justice for whom it is named. Echohawk—an NRDC Board member for nearly 30 years—describes the honor as “overwhelming.” But to colleagues and admirers, it’s well deserved. “John is one of the foremost advocates for Native American rights of his generation,” says NRDC Chief Counsel Mitch Bernard, who has known Echohawk for decades. “He is a man of great fortitude, patience, and persistence, with a keen, lived understanding of the sacred nature of Native American culture and land.”

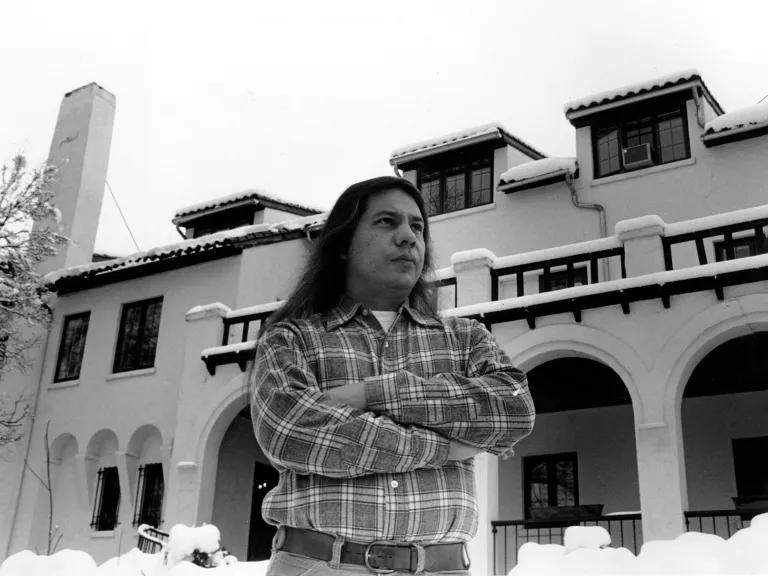

Echohawk standing outside the building that houses the Native American Rights Fund—which he founded in 1970—in Boulder, Colorado, March 27, 1984

Jerome Delay/Associated Press

Holding the U.S. government to its word

From the beginning, Echohawk and NARF have emphasized the role of tribal sovereignty in federal Indian law, regularly reminding courts and Congress that the U.S. government is bound by the language of the many treaties it has struck with Native Americans over nearly two and a half centuries—regardless of the age of those treaties.

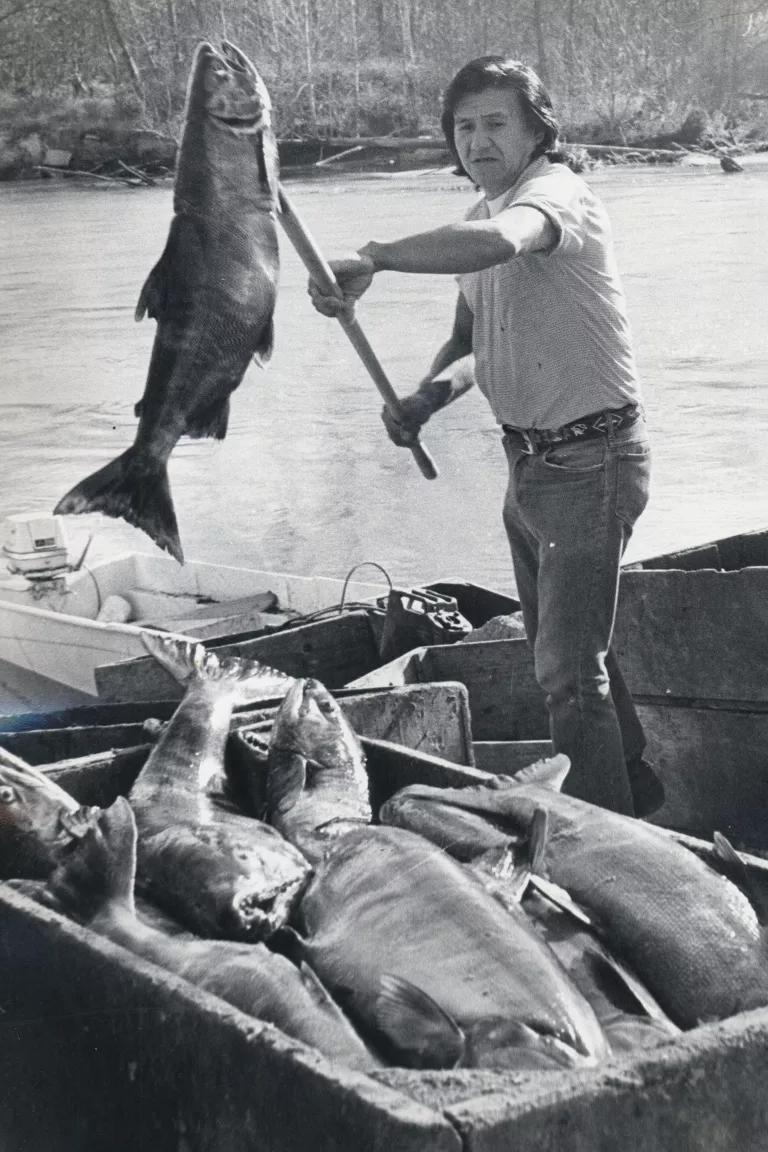

One landmark case that applied this principle was United States v. State of Washington (known more commonly as “the Boldt Decision”), one of NARF’s many cases that changed the course of Native American legal history. For millennia, tribes of the Pacific Northwest had relied on the waters of Puget Sound for one of their most sacred foods and a central element of their culture: salmon. Yet their fishing traditions, protected in numerous treaties, came under threat as the state of Washington—frequently aided by the courts—repeatedly and systematically hindered the ability of tribes to fish in their “usual and accustomed” way, violating agreements dating back to the 19th century and introducing discriminatory regulations. By the 1970s, Native Americans were only taking in about 2 percent of the annual salmon harvest.

The tribes came to Echohawk and NARF and asked them to take the case. NARF’s legal team knew that the government owed the tribes more than just the ability to fish without hindrance. In fact, the team successfully argued, the tribes were entitled to control one-half of the fishery—which can number as many as four million salmon per season—and to share regulatory authority with the state government.

“So we started sharing that big salmon fishery with the state of Washington,” Echohawk says. “And that [decision] got affirmed by the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals and, eventually, the U.S. Supreme Court.” Just as important as the restoration of tribal fishing rights, he notes, was the precedent set by the case: “Everybody came to understand that these treaties were not ancient history—that they were still the supreme law of the land.”

As the Native American Civil Rights Movement of the 1970s burgeoned, and as protests against the continued injustices toward Native Americans became more visible across the country, NARF and Echohawk found that they had the ear of lawmakers—and even presidents. They took every opportunity that came their way to redress these injustices. More than a dozen years after an act of Congress “terminated” the Menominee Indian Tribe of Wisconsin—dissolving the tribe’s reservation and forcing members to remake their lives in unfamiliar cities—NARF successfully lobbied Congress to restore the Menominees’ tribal status and sovereignty. And when the Passamaquoddy Tribe and Penobscot Nation wanted to sue the state of Maine for unlawfully taking control of tribal land and affairs, NARF pointed to a federal law passed back when George Washington was president that prohibited such seizures.

“The Intercourse Act of 1790 said there can be no transactions with tribes over land unless they are approved by the federal government,” Echohawk says, reflecting on the illegitimate transfer of millions of acres of tribal land to the state, taken over the course of many years. These transactions had never been ratified by Congress, NARF argued—and it won, first in District Court and then later in the Court of Appeals.

Meanwhile, Maine’s government knew it didn’t have a leg to stand on as the tribes readied their case for the U.S. Supreme Court. “So President Carter called a big meeting in the White House for us to come together and talk about a settlement, instead of going to the Supreme Court and [having] a big winner and a big loser.” The Passamaquoddy and Penobscot came away from the agreed-upon settlement “with a huge part of their land back, a whole lot of money, and federal recognition.”

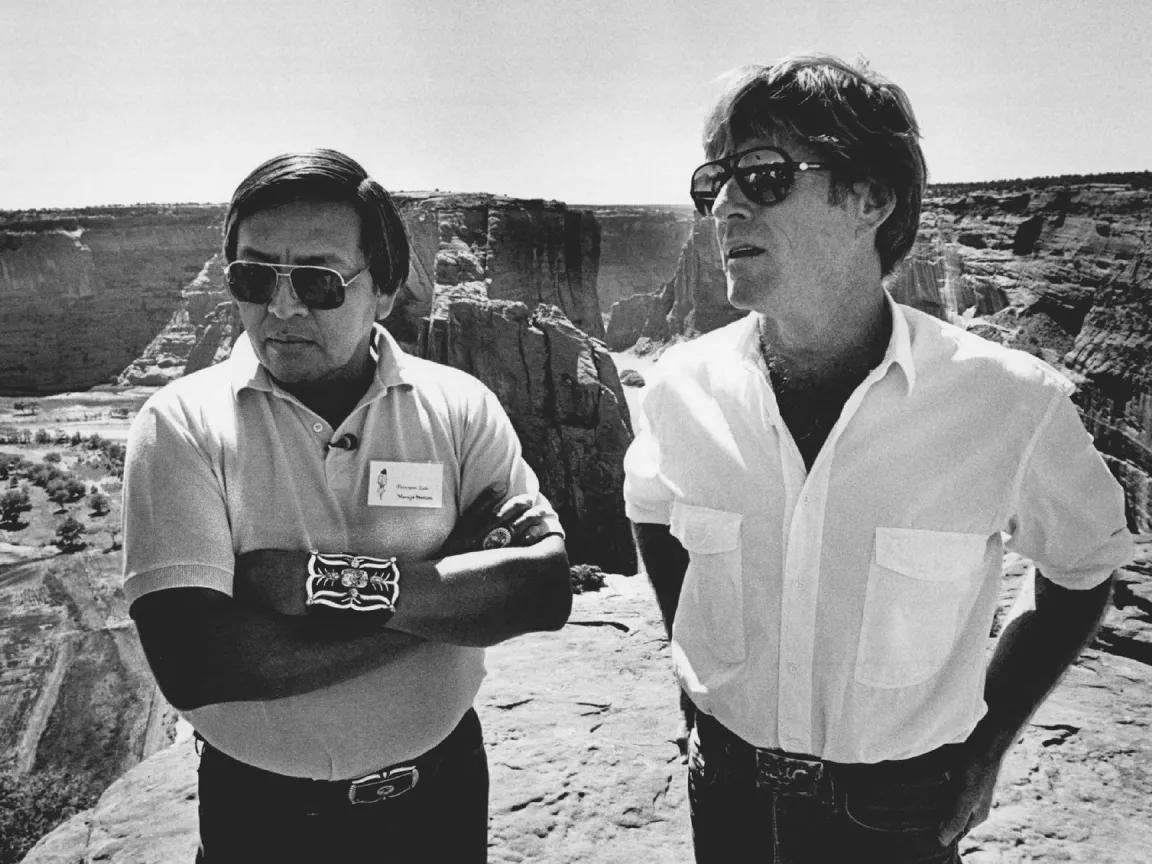

Finding new allies

Another auspicious meeting attended by Echohawk resulted in his longtime affiliation with NRDC. In the mid-1980s, Echohawk’s friend, the actor and NRDC Board member Robert Redford, was hoping to bridge two avenues of his renowned activism: support for Native American rights and support for the environment. “He was really concerned about how there was a lack of understanding by environmental organizations of tribes,” Echohawk says. “So he helped put together a big meeting at the Navajo Nation, and brought together tribal leaders and organization leaders to get to know each other.”

The meeting got off to an uncertain start. When tribal representatives began to describe their tribes as sovereign governments, Echohawk recalls with a laugh, “some of the environmental leaders said, ‘You’re governments? But we sue governments!’ And we said, “Wait a minute, wait a minute, we’re not the same kind of government!’ And so then we talked about our religions and our cultures, protecting the environment—the things we believe in.” Echohawk was asked to join NRDC’s Board shortly thereafter and accepted.

“To be in the presence of John Echohawk fills me with humility, gratitude, and respect,” Bernard says. “His integrity and record of achievement are a constant reminder of the importance of NRDC's mission: to protect the planet and, in doing so, to vindicate the rights of all cultures and people, especially those who have endured, and continue to endure, the deepest burdens.”

Echohawk speaking during the NRDC board meeting in Santa Monica, California, February 10, 2023

Lauren Justice for NRDC

Echohawk has been in practice long enough to know that American politics is a pendulum. Speaking of NARF’s record in the Supreme Court, he observes that “we did pretty well in the ’70s and ’80s. But then, beginning in the ’90s, with the change in the makeup of the court, we saw that the tribes weren’t winning as many cases as they used to.” With that said, he notes that Native Americans have been able to find allies at both ends of the political spectrum. As for his community’s dealings with the current White House, Echohawk—who cofounded NARF back when Richard Nixon was president—minces no words. “Tribal leaders agree that this is the best administration we’ve ever had,” he says, in no small part because “they’ve got a number of Native Americans in key positions who know the issues.”

Looking back on a 50-year career fighting for tribal sovereignty—and with it, tribal stewardship of land, water, and other cultural and natural resources—John Echohawk rightly sees a record of which he can be proud. He and his NARF colleagues understood the issues because of their lived experiences. They understood the law, having studied it closely. “We just had to bring it to the courts, since we didn’t really have lawyers before then,” he says. “And it’s made all the difference.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

The Unlikely Takedown of Keystone XL

The Future Has Spoken: It’s Time to Shut Down DAPL and Stop Line 3

From Dams to DAPL, the Army Corps’ Culture of Disdain for Indigenous Communities Must End