Biden’s Clean Trucks Proposal Is Too Slow on Ditching Dirty Diesel

Communities in high-traffic corridors need trucks to stop polluting their air—and they need it now.

According to a 2017 EPA study, the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States is from the transportation sector, particularly from burning fossil fuel for cars, trucks, and planes.

No matter how hard Ivonne Gutierrez works to keep the children safe at the day care center she runs out of her home, air quality is a constant worry. She lives in Armourdale, a predominantly Latino and working-class neighborhood on the south side of Kansas City, Kansas, that is also home to several polluting industries. Everything from scrap metal shredders to chemical manufacturing facilities to coal-fired power plants dot the area, and highways and rail yards surround the neighborhood on all sides.

Earlier this year, the Kansas City–based environmental advocacy group CleanAirNow invited representatives from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to witness the pollution outside Gutierrez’s home for themselves. It didn’t take long for them to see the problem. All day long, semi-trucks pump exhaust into the air as they drive by her home or spend time idling in the parking lot next door, just feet from her fenceline. “It was important for us to show the EPA that community members actually live in these neighborhoods,” says CleanAirNow’s co-executive director, Atenas Mena. “The families that live here can’t leave. They have to breathe this, 24/7.” It’s time, she says, for the EPA to treat this truck pollution as the public health crisis it is.

But so far, the Biden administration is falling short.

The strongest option in EPA’s Clean Trucks Rule, proposed in March, would require manufacturers to make modest improvements to their diesel-combustion engines, which emit dangerous amounts of smog-forming particulate matter and planet-warming greenhouse gases. The rule applies to a broad category of heavy-duty trucks—ranging from big rigs and school buses to short-haul delivery vans—and would be the first update to federal truck standards in more than 20 years.

But the administration’s proposal doesn’t go far enough to clean up combustion engine vehicles and misses the mark on what environmental, health, and labor groups say is essential to curbing truck pollution and its widespread public health hazards: a swift transition to zero-emission vehicles.

To add insult to injury, the U.S. Postal Service, in defiance of the Biden administration, recently placed an order for tens of thousands of new gasoline-powered and polluting delivery trucks for its fleet. These inefficient new vehicles will burn billions of dollars more in fuel than electric models and emit 20 million metric tons of carbon pollution over a 20-year lifetime. NRDC, together with the United Auto Workers, is currently challenging this in court.

“Electric vehicles are here now,” Mena says. The shift “needs to be aggressive, it needs to be stringent, and it needs to be a priority. We can’t wait any longer.” Now, the Moving Forward Network—a national coalition led by environmental justice groups that is working to clean up the freight system of dirty tankers and trucks—is hoping to convince the EPA to strengthen its proposal before it finalizes the rule later this year.

Diesel Death Zones

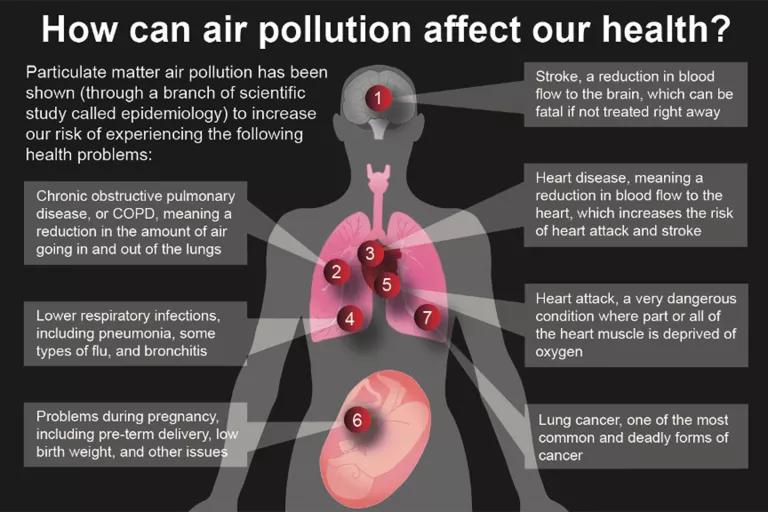

Trucks are by far the worst polluters on the road. They usually run constantly and largely burn diesel fuel, which is less refined and contains more pollutants than gasoline. This is why, despite accounting for just 4 percent of U.S. vehicles, trucks emit 23 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, half of all nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, and 60 percent of fine particulate matter. Even low levels of these air pollutants are linked to a list of health risks, including more frequent and severe asthma attacks, cardiac disease, and cancer.

Researchers have found that an increase of just 10 micrograms per cubic meter of air of PM 2.5—which is airborne particulate matter that’s small enough to enter the bloodstream through the lungs—raises the risk of someone dying from heart disease by 10 percent. In fact, the health impacts associated with chronically breathing in exhaust-choked air are so dire that areas of high truck traffic have been dubbed “diesel death zones” by environmental justice advocates—and they’re far more likely to sit in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color.

A 2021 study analyzed how levels of the tailpipe pollutant nitrogen dioxide shifted in major U.S. cities in the first months of the pandemic. Prior to COVID-19, the census tracts with the most residents of color faced nearly three times the nitrogen dioxide pollution as those with the highest percentages of white residents, but the researchers found that stark disparities persisted even as traffic decreased during lockdowns. Even with fewer vehicles out on the road, census tracts with the greatest percentages of people of color continued to face 1.5 times the nitrogen dioxide levels.

“It’s historical racist policies that put high truck traffic into these neighborhoods,” says NRDC senior advocate Patricio Portillo. Making matters worse, residents in high-traffic corridors, like Armourdale, often face pollution from several sources.

After EPA staffers saw the semis idling outside Gutierrez’s home and day care, the next stop on CleanAirNow’s tour was just five blocks away, where Armourdale’s largest scrap metal recycling facility spews heavy metal-laden smoke into the air. Multiple pollution sources, often combined with limited access to health care and healthy food, can compound within a community to create staggering health disparities. In fact, life expectancy for Armourdale residents is 22 years shorter than for people living in other parts of the county. “That’s a lifetime,” Mena says.

Federal Truck Rule Stalls Behind

The EPA, under administrator Michael Regan, has made big promises to prioritize environmental justice. But even though the agency’s own data show truck pollution harms communities unevenly, its latest rule continues to appease industry interests by failing to mandate the phaseout of diesel-combustion engines, a transition that’s not only feasible, but also cost-effective. In a recent letter to the EPA, the Moving Forward Network urged the agency to make it happen by 2035.

A regulatory loophole also exists within the EPA’s proposed limits on NOx emissions. Because the standards measure emissions as an average across all the vehicles a manufacturer sells, an automaker can avoid improving its highest-polluting engines so long as a higher percentage of zero-emission vehicles brings the average down. “It will become easier and easier for them to hit the bare minimum, essentially,” says Portillo.

Speaking at one of the rule’s public comment hearings, Amy Goldsmith, the New Jersey director for Clean Water Action, said, “While new motor engines have better pollution controls than older models, there's little difference over time when you're living and breathing it as a driver in the cab of a truck or a local resident standing at the curb and sucking in the fumes.”

A recent study commissioned by the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund found that electric trucks and buses could reach cost parity with diesel for many segments of the market by 2027, the year Biden’s clean trucks rule is set to go into effect. The researchers also say that lower maintenance and fuel costs could have purchasers recouping their initial investment within one to two years. Continued volatility in the global oil market, as well as the declining cost of electric vehicle batteries, might drive that estimate even lower.

In recent years, some states have been picking up the federal government’s slack on truck engine standards. California, for example, has adopted two health-protective measures: the Advanced Clean Trucks rule, which requires manufacturers to sell an increasing percentage of zero-emission trucks each year, and the Heavy-Duty Omnibus rule, which sets stricter standards on air pollutants from new fossil fuel trucks. Both are more ambitious than the EPA’s latest clean trucks proposal.

The private sector is also speeding ahead, with corporate giants like Ikea, UPS, and FedEx all making headlines for beginning their transition to zero-emission fleets. Meanwhile, the number of makes and models for zero-emission vehicles continues to rise. Market research out of the clean transportation group Drive to Zero says that more than 100 models of medium- and heavy-duty zero-emission trucks from dozens of manufacturers are already commercially available.

Ultimately, the federal proposal shows that the EPA is out of touch with both the momentum of the market and the action being taken by states. “This issue is about the right to breathe clean air,” Portillo says. “It’s a crisis in a lot of communities. They needed these protections yesterday.” Gutierrez most certainly agrees.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

What Biden Should Get Done on Day One (or Close to It)

If You Care About Climate Change, Then You Care About the Farm Bill

How to Make an Effective Public Comment