Gibbstown LNG Terminal: A Catastrophe Waiting to Happen

Imagine hundreds of trucks and train cars filled with highly explosive fuel coming through your community every day. These Pennsylvanians and New Jerseyans are fighting to extinguish the project—for good.

A rail yard in Gibbstown, New Jersey

Photographs by Sahar Coston-Hardy for NRDC

UPDATE: On April 24, 2023, the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) denied the renewal of a permit for Energy Transfer Solutions, a subsidiary of New Fortress Energy, to transport LNG by rail from Wyalusing, Pennsylvania, to Gibbstown, New Jersey. The project to construct an LNG terminal in Gibbstown could still move forward, however, unless the DOT suspends the federal LNG-by-rail rule issued during the Trump administration.

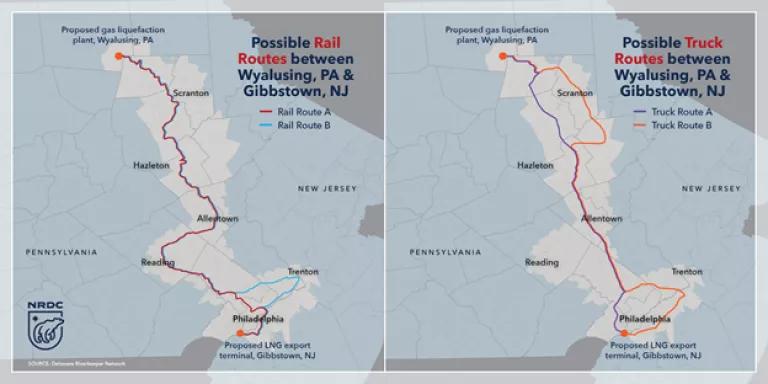

Across the Delaware River from the Philadelphia International Airport sits roughly 300 acres of empty but heavily polluted land. The plot is quiet at the moment, but if plans move forward to construct a terminal here to export liquefied natural gas (LNG), more than 1,650 trucks and two 100-car trains carrying this highly explosive fuel could pass through the area every day. LNG has a history of large explosions on roadways (including a 2020 crash in eastern China that killed 19 people and injured more than 170), but the fuel has never before traveled en masse by rail.

“Rather than create an actual pipeline that we know how to fight and we know how to regulate, they created this horrendous series of shipments by truck and rail,” says NRDC senior attorney Kimberly Ong, who directs the Northeast Fossil Free team. “It’s like nothing we’ve ever seen before.” Ong sees the terminal as a way for companies to test the viability of expanding LNG facilities on the East Coast. This is just the type of infrastructure that the U.S. fossil fuel industry is currently pushing to fast-track under the guise of “energy independence,” in response to Russia’s war on Ukraine.

The project by developer New Fortress Energy proposes to build a plant to liquefy fracked gas in Wyalusing, Pennsylvania, before shipping it nearly 200 miles to a deepwater port in Gibbstown, New Jersey, where the LNG would then depart for Ireland, Puerto Rico, and other overseas locations. Although a recent court settlement put the development of the Wyalusing plant on hold for at least several months, advocates are not letting up.

Delaware Riverkeeper Network’s deputy director, Tracy Carluccio, in Gibbstown on March 29, 2022

“The people of Wyalusing should rest easier today, but the project is far from over,” says Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of Delaware Riverkeeper Network, an environmental group headquartered about 20 miles upstream from Philadelphia that’s been leading local advocacy efforts. There’s a possibility that New Fortress Energy could secure a new air permit and begin construction in the fall. Carluccio says several pieces of the project are also in different stages of permitting under various agencies, which adds confusion to an already convoluted and, at times, secretive process.

But one thing remains clear: LNG-filled trucks and trains pose unreasonable risks to communities. In comments submitted to the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration in 2020, a coalition of environmental groups estimated that just 22 train tank cars filled with LNG hold the same amount of energy as the Hiroshima bomb. The fuel also emits climate-destroying methane at every step of its production process, including during transportation. To boot, the site for the terminal at Gibbstown is the former DuPont Repauno Works plant, one of the largest PCB contamination sites on the Delaware River. Disturbing the ground here could release these carcinogens into local ecosystems, soils, and the river.

Fearing for their immediate safety, residents along the project’s proposed paths in Pennsylvania and New Jersey are fighting the dangerous project and the myriad other issues the project would exacerbate, including environmental injustice, fracking, PCB pollution, and climate change. Here’s what they have to say about it.

Marcus Sibley

Burlington, New Jersey

Marcus Sibley thinks that everyone—everyone—should speak out against the LNG facility. But before that can happen, Sibley, who is the environmental and climate justice chairman for the New Jersey NAACP and the president of the organization’s South Burlington County branch, says people need to know about the issue. He speaks of two extremes: Those people who are very aware of the plan to transport LNG through the state and those who live very close to the potential LNG routes but have no clue about the project. Sibley and his partners are making sure that New Jerseyans all along the way—from Trenton and Camden to Woodbury and Gibbstown—have an opportunity to learn of the threats that “bomb trains,” along with LNG trucks on highways and other local roadways, pose to their communities. He says, “Even if people aren't really well versed in environmental justice or climate, they have definitely heard of things exploding.”

Activists are holding an educational summit in Camden this month, where speakers hope to convey the magnitude of danger the terminal would bring and encourage residents to join the fight. Sibley says, “I'm focusing on the message of ‘you live here, this is coming here, there's a good chance you could be in the blast radius.’”

Sibley is emphatic about the terminal being a zero win for the community. “It is a case of exploitation on a very grand scale. People have dealt with bad before, but not this kind of bad,” he says. “It will be very important for these communities to speak out against the project because once it happens, it's too late. Once it’s here, it’s too late.”

Gina Corola

Haddonfield, New Jersey

Fighting the Gibbstown LNG terminal is far from Gina Corola’s first local environmental battle. The retired IT professional has been working alongside the Delaware Riverkeeper Network for about 30 years, fighting proposed coal plants, corporate polluters, and more. Her role is to get the information out there, go to hearings, and testify. Corola’s efforts, connection to the area, and knowledge of local politics have also led her to become the coordinator of Delaware River issues for the New Jersey chapter of the Sierra Club.

Like others in this fight, she’s been working on getting mayors and town council members to pass resolutions opposing the project. “Resolutions, of course, have no legal teeth, but at least they’re something we can show the governor and say, ‘Hey, squash this thing,’ you know?”

In her hometown of Haddonfield, however, Corola has run into some resistance, with council members saying that they can’t go around signing resolutions for everything that comes down the pike. “Well, no, of course not,” she says. “But this one’s extremely important. We're not asking them to sign a resolution against street vendors or something. We're asking for something that we need to protect neighborhoods, protect the schools.”

Corola persists because she sees getting Governor Phil Murphy on board as critical to the fight, but she still worries that it’ll take a disaster for people to truly understand LNG’s dangers and to prompt them to do something about it. Corola says that most people don’t grasp just how big of a fireball a jackknifed LNG truck on nearby Interstate 295 (one likely route for highway transport) would ignite. But she’s not giving up hope. “We just have to keep pushing,” she says. “We’ve got to make people aware of what's coming their way.”

Fermín Morales

Philadelphia

Although Fermín Morales moved from Puerto Rico to Philadelphia in the 1960s when he was three years old, he retains a strong connection to his home island. As part of a community group called Philly Boricuas, Morales encourages the city’s Puerto Ricans to advocate for local issues as well as those that affect their relatives on the island. The proposed LNG terminal threatens both populations.

According to maps of the projected routes, LNG-filled trucks and trains would barrel through some of Philly’s most densely populated areas, including Morales’s Fairhill neighborhood—“the poorest in the city,” he says. This would put hundreds of thousands of Philadelphians within the blast zone multiple times every day. The terminal will then ship some of the LNG to New Fortress Energy’s San Juan terminal in Puerto Rico, furthering the island’s dependence on imports of dirty energy.

Morales, an electrician and long-standing member of his local union, finds it maddening that companies continue to develop new fossil fuel projects while the potential of renewables, especially in solar-friendly Puerto Rico, continues to go underrealized. “They know the damage that it does, but they don't care,” he says of the natural gas industry. “They're not taking climate change seriously. It's all about profits.”

Morales believes a complete societal transformation is necessary, but in the meantime, he’s going to fight to keep his community safe. In the hopes that Philadelphia will pass a resolution against the LNG proposal, Morales and fellow Boricuas members have been taking to the streets, passing out informational flyers, gathering petition signatures, and working to gain support in city hall. “You’ve got to reach the people who are not going to be on Facebook or Twitter,” Morales says. “You’ve got to put this issue right in front of their faces, even if they get mad. You have to confront people so they understand the damage that it's going to do, and so we can stop it once and for all.”

Zoe Leach

Lawrence Township, New Jersey

Zoe Leach first caught wind of the LNG project last year after attending a climate rally in North Jersey. Eager to volunteer her time and skills to climate action—what she calls her number one issue—Leach linked up with some of the rally’s organizers, who then shared details about how one of the possible LNG transport routes to Gibbstown would run by Trenton, the state capital. Leach lives in Lawrence Township, which borders Trenton to the north. Before long, she was asking Trenton city council members to back a resolution opposing the project, and in early December, the council unanimously voted to do just that.

“It just seems like a no-brainer to me to try to get folks behind rejecting the project,” Leach says, adding that community resolutions are useful in that they can show a unified opposition to something and communicate a sense of urgency to decision makers, such as Governor Murphy. She says she’s optimistic that the governor will follow through on his December 2020 intention to prevent the Gibbstown port being used for LNG transport, despite his vote in favor of the terminal’s construction (which could potentially serve other purposes) earlier that same month.

Leach, who is a case management nurse in a Trenton acute care hospital, is also advocating for first responders for whom she says the LNG project poses an incredible threat. In the event of an accident, EMTs, health care workers, and other first responders—already exhausted after two years of the pandemic—would face an enormous burden of responsibility. “They're burned out and understaffed, and they’ve already been through so, so much,” she says. “And then you're just gonna add this issue on top of it?”

Jim Stewart

National Park, New Jersey

About six miles up the Delaware from Gibbstown is National Park, New Jersey, where Jim Stewart, a 77-year-old veteran, has lived for 30 years and where he raised his five children. The community of 3,000 is already dealing with exceedingly high levels of PFAS in its drinking water, due to pollution from the nearby Solvay chemical manufacturing plant, and Stewart believes some of his recent health issues might be linked to it. So when he first learned about the plans for the LNG terminal early last year, his immediate concern was safety. Stewart couldn’t wrap his head around the approval of a special permit to transport such a dangerous fuel—a plan he calls “outrageous and ridiculous.” The more he dug, the more he learned about New Fortress Energy’s attempt to hide its intentions from the public to export LNG from the terminal. The more he learned, the more he wanted to fight back.

Stewart started by advocating for the Borough of National Park to oppose the project, and after securing that, he and other local activists are now pushing neighboring municipalities to do the same. According to Stewart, just about everybody who knows about the project is worried—the problem is that not many people know about it. “We've taken on the task of trying to get the word out to everyone we can, every chance we can,” he says.

On top of the project’s potential for igniting fiery explosions in the region, Stewart is also concerned about the terminal’s even more widespread and longer-term dangers. “The expansion of LNG, of oil and gas, is just something we can't accept. We can't continue to invest in this infrastructure if we're going to end the climate crisis,” the grandfather of five says. “We've got to move, and we've got to move now.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Protect Your Community from “Bomb Trains”

These New Jerseyans Want to Bring “Bomb Trains” to a Halt

The Unlikely Takedown of Keystone XL