Spare Yourself the Guilt Trip This Earth Day—It’s Companies That Need to Clean Up Their Acts

More and more states are looking to pass a new kind of recycling law that asks manufacturers to foot the bill for the waste created by their products.

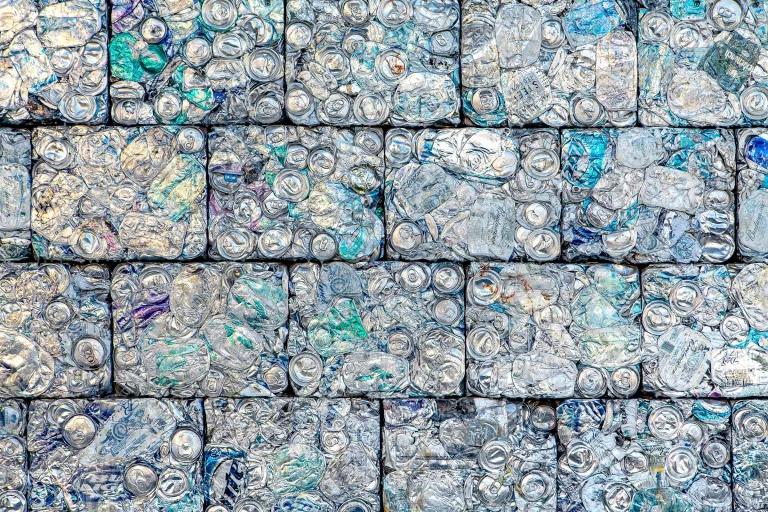

Bales of plastic sit ready to be processed and recycled.

Coined in the 1970s, the classic Earth Day mantra “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle” has encouraged consumers to take stock of the materials they buy, use, and often quickly pitch—all in the name of curbing pollution and saving the earth’s resources. Most of us listened, or lord knows we tried. We’ve carried totes and refused straws and dutifully rinsed yogurt cartons before placing them in the appropriately marked bins. And yet, nearly half a century later, the United States still produces more than 35 million tons of plastic annually, and sends more and more of it into our oceans, lakes, soils, and bodies.

Clearly, something isn’t working, but as a consumer, I’m sick of the weight of those millions of tons of trash falling squarely on consumers’ shoulders. While I’ll continue to do my part, it’s high time that the companies profiting from all this waste also step up and help us deal with their ever-growing footprint on our planet.

An investigation last year by NPR and PBS confirmed that polluting industries have long relied on recycling as a greenwashing scapegoat. If the public came to view recycling as a panacea for sky-high plastic consumption, manufacturers—as well as the oil and gas companies that sell the raw materials that make up plastics—bet they could continue deluging the market with their products.

There are currently no laws that require manufacturers to help pay for expensive recycling programs or make the process easier, but a promising trend is emerging. Earlier this year, New York legislators Todd Kaminsky and Steven Englebright proposed a bill—the “Extended Producer Responsibility Act”—that would make manufacturers in the state responsible for the disposal of their products.

Other laws exist in some states for hazardous wastes, such as electronics, car batteries, paint, and pesticide containers. Paint manufacturers in nearly a dozen states, for example, must manage easy-access recycling drop-off sites for leftover paint. Those laws have so far kept more than 16 million gallons of paint from contaminating the environment. But for the first time, manufacturers could soon be on the hook for much broader categories of trash—including everyday paper, metal, glass, and plastic packaging—by paying fees to the municipalities that run waste management systems. In addition to New York, the states of California, Washington, and Colorado also currently have such bills in the works.

“The New York bill would be a foundation on which a modern, more sustainable waste management system could be built,” says NRDC waste expert Eric Goldstein.

In New York City alone, the proposed legislation would cover an estimated 50 percent of the municipal waste stream. Importantly, it would funnel millions of dollars into the state’s beleaguered recycling programs. This would free up funds to hire more workers and modernize sorting equipment while also allowing cities to re-allocate their previous recycling budgets toward other important services, such as education, public parks, and mass transit.

The bills aren’t about playing the blame game—they are necessary. Unsurprisingly, Americans still produce far more trash than anyone else in the world, clocking in at an average of nearly 5 pounds per person, every day—clogging landfills and waterways, harming wildlife, contributing to the climate crisis, and blighting communities. As of now, a mere 8 percent of the plastic we buy gets recycled, and at least six times more of our plastic waste ends up in an incinerator than gets reused.

It’s easy to see why. Current recycling rules vary widely depending on where you live—and they’re notoriously confusing. Contrary to what many of us have been told, proper recycling requires more than simply looking for that green-arrowed triangle, a label that may tell you what a product is made out of and that it is recyclable in theory, but not whether that material can be recycled in your town—or anywhere at all. About 90 percent of all plastic can’t be recycled, often because it’s either logistically difficult to sort or there’s no market for it to be sold.

That recycling marketplace is also ever changing. When China, which was importing about a third of our country’s recyclable plastic, started refusing our (usually contaminated) waste streams in 2018, demand for recyclables tanked. This led to cities as big as Philadelphia and towns as small as Hancock, Maine, to send even their well-sorted recyclables to landfills. Municipalities now had to either foot big bills to pick up recyclables they once sold for a profit or shutter recycling services altogether.

According to Goldstein, New York’s bill has a good shot of passing this spring—and it already has the support of some companies that see the writing on the wall, or as the New York Times puts it, “the glimmer of a cultural reset, a shift in how Americans view corporate and individual responsibility.” If the bill does go through, New Yorkers could start to see changes to both local recycling programs and product packaging within a few years.

What makes these bills so groundbreaking isn’t that they force manufacturers to pay for the messes they make, but that they could incentivize companies to make smarter, less wasteful choices in the first place.

New York’s bill, for instance, could help reward more sustainable product design. A company might pay less of a fee if it reduces the total amount of waste of a product, sources a higher percentage of recycled material, or makes the end product more easily recyclable by, say, using only one type of plastic instead of three.

“Producers are in the best position to be responsible because they control the types and amounts of packaging, plastics, and paper products that are put into the marketplace,” Goldstein says.

Bills like these embody the principles of a circular economy—that elusive North Star toward which all waste management policies should point. By encouraging companies to use more recycled materials, demand for recyclables goes up and the recycling industry itself is revitalized. What gets produced gets put back into the stream for reuse.

If widely adopted, we could significantly reduce our overall consumption and burden on the planet. With less paper used, more forests would stay intact—to continue to store carbon, filter air and water, and provide habitat for wildlife and sustenance for communities. With less plastic produced, less trash would clog oceans and contaminate ecosystems and food supplies. In turn, we’d give fossil fuels even more reasons to stay in the ground, where they belong.

That would be my Earth Day dream come true—with little hand-wringing of fellow guilt-stricken individuals required.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

What Are the Solutions to Climate Change?

Flooding and Climate Change: Everything You Need to Know

How You Can Stop Global Warming