U.S. Livestock Antibiotic Use Is Rising, Medical Use Falls

For the last decade, the FDA has been urging the industrial meat industry to use antibiotics more wisely. That makes it important to question why livestock sales have risen the past two years.

A microbiologist examining colonies of the pathogenic MRSA (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus) bacteria on a blood agar culture plate.

Co-authored with Eili Klein and Alisa Hamilton, Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy

Experts predict that by 2050 there will be up to 10 million deaths per year from drug-resistant infections, worldwide, unless policymakers take more effective actions to protect us. Antibiotic-resistant bacteria, sometimes called ‘superbugs’, cause more than 2.8 million infections and contribute to between 35,000 and 162,000 deaths in the U.S. each year.

Use of any antibiotic anywhere can add to the resistance that emerges to any other antibiotic anywhere else, making it especially important to avoid inappropriate or unnecessary uses. Curbing resistance demands much wiser use of these precious medicines. That is especially true on farms and in human medicine—the two largest categories of use, by far.

The intensive use of antibiotics in livestock production has long been a public health concern. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) spent the last decade calling on U.S. livestock industries, mostly on a voluntary basis, to use antibiotics more judiciously. However, the latest FDA data appear to confirm that antibiotic overuse continues. Livestock sales have risen for two straight years, after a brief decline from 2015 to 2017.

By themselves, the FDA sales data are an insufficient proxy for clearly understanding antibiotics use on U.S. farms and ranches. Unfortunately, no U.S. system exists to comprehensively track the actual use of medically important antibiotics. A system like that could generate side-by-side reports comparing how these precious drugs are being used in different settings. Collection of antibiotic use data at the farm level would provide the granularity needed to address how often and how many antibiotics U.S. farms are using, and why they are being used.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the “slow moving” pandemic of antibiotic resistance is best addressed using a “One Health” approach. That kind of an approach, for example, would be one that holistically tracked antibiotic use, along with levels of resistance, in human populations, in animals, and in the environment. Since 2009, the FDA has reported annual sales of livestock antibiotics but no information on veterinary prescriptions or orders; human sales data also are not reported. Meanwhile, the CDC now issues annual reports on antibiotic prescriptions in human medicine, but these releases do not provide national data on medical antibiotic sales.

Our New Analysis. For the third time since 2017, NRDC and Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy (CDDEP) have teamed up to fill in critical data gaps around antibiotic use in the United States. Table 1 and the accompanying figure include both the FDA’s annual data on livestock sales of medically important antibiotics for 2009 to 2019, along with estimated use of the same drugs in human medicine. To estimate human use, CDDEP used data obtained from IQVIA, a private company that directly collects outpatient antibiotic prescribing information across the U.S. Total medical use of antibiotics was approximated by combining outpatient data with estimates of hospital prescriptions.

Doing a side-by-side comparison of the same medically important antibiotics sold for livestock use and used in human medicine allows for better appreciation of key differences and patterns. Use of antibiotics in human medicine has remained consistent since 2009. It even declined slightly since 2017, despite the year-on-year increase in the U.S. population. By contrast, sales of these same drugs for use in livestock increased 11.3% from 2017 to 2019, from 5.6M kg to 6.2M kg. Livestock sales are now nearly double the sales for human medicine (6.19M kg vs. 3.30M kg).

From 2009, livestock antibiotic sales increased to a peak in 2015, before falling in 2016 and 2017. This was the period when FDA first urged the livestock sector to stop marketing and selling medically important antibiotics in animal feed for the purpose of growth promotion. Growth promotion use of feed antibiotics was made illegal in January 2017. All remaining feed uses were also put under veterinary oversight, meaning that a veterinarian has to write a prescription or veterinary “feed directive” before a feed mill will mix medically important antibiotics into animal feed and distribute it to producers. Under these feed directives, however, many livestock antibiotics continue to be fed to herds of animals on a routine basis for the so-called disease prevention, even when there are no sick or diseased animals.

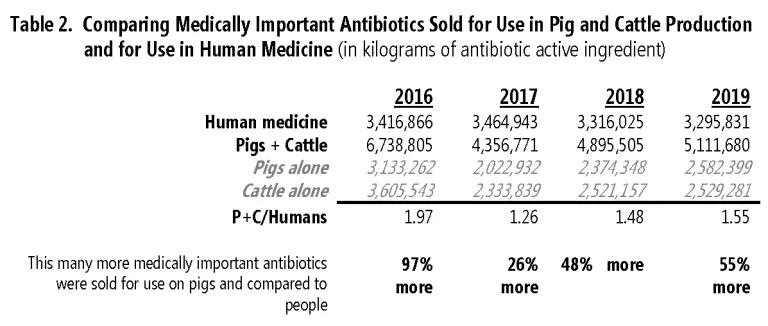

The net increase in livestock sales since 2017 is entirely due to more antibiotics being sold for use in pig and cattle production. Over those two years, pig sales rose by about 560,000 kg, or nearly 28%, as illustrated in Table 2. Sales for cattle also rose, by a more modest 8%. Sales of medically important antibiotics for pigs and cattle combined are 55% higher than sales of those medicines for human patients.

As we noted earlier, current FDA reporting of antibiotic sales is not sufficient. Ideally, the FDA would offer more context to sales figures by also reporting the relative size of the animal population under production. That is what FDA proposed to do back in 2017, but has failed to follow through.

Using the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Quickstat tool, we looked up the number of mature pigs slaughtered each year in the U.S. from 2017 to 2019. Total pigs slaughtered is a reasonable proxy for the size of the pig population most likely to receive whatever pig antibiotics were sold that year. We found data indicating the size of this pig population increased from 2017 to 2019 by about 7%. Therefore, higher levels of production alone cannot explain a 28% jump in pig antibiotic sales.

FDA Must Do Better. Immediately, the FDA should follow through and begin reporting antibiotic sales adjusted by the size of the animal population most likely to receive those drugs as it proposed in 2017. These data should also be integrated into a federal system that comprehensively tracks, and then provides fully-integrated reports on both antibiotic use and resistance in people, the environment, and in animals—especially farm animals.

The CDC states that 75% of dangerous new infections, including pandemics, spill over from animals to human populations. These animal-borne threats include viruses as well as new forms of antibiotic resistance genes and the multi-drug resistant superbugs that carry them. Pandemic preparedness and public health protection should be our nation’s foremost priority. We must therefore invest to robustly to track antibiotic resistance and antibiotic use wherever it occurs.